When you pick up a generic prescription, you expect it to be cheaper than the brand-name version. And for the most part, it is. But what you might not realize is that the price of your generic drug can swing wildly from one year to the next - sometimes dropping sharply, other times jumping by hundreds of percent - even if nothing about the pill itself has changed.

How Generic Drug Prices Normally Work

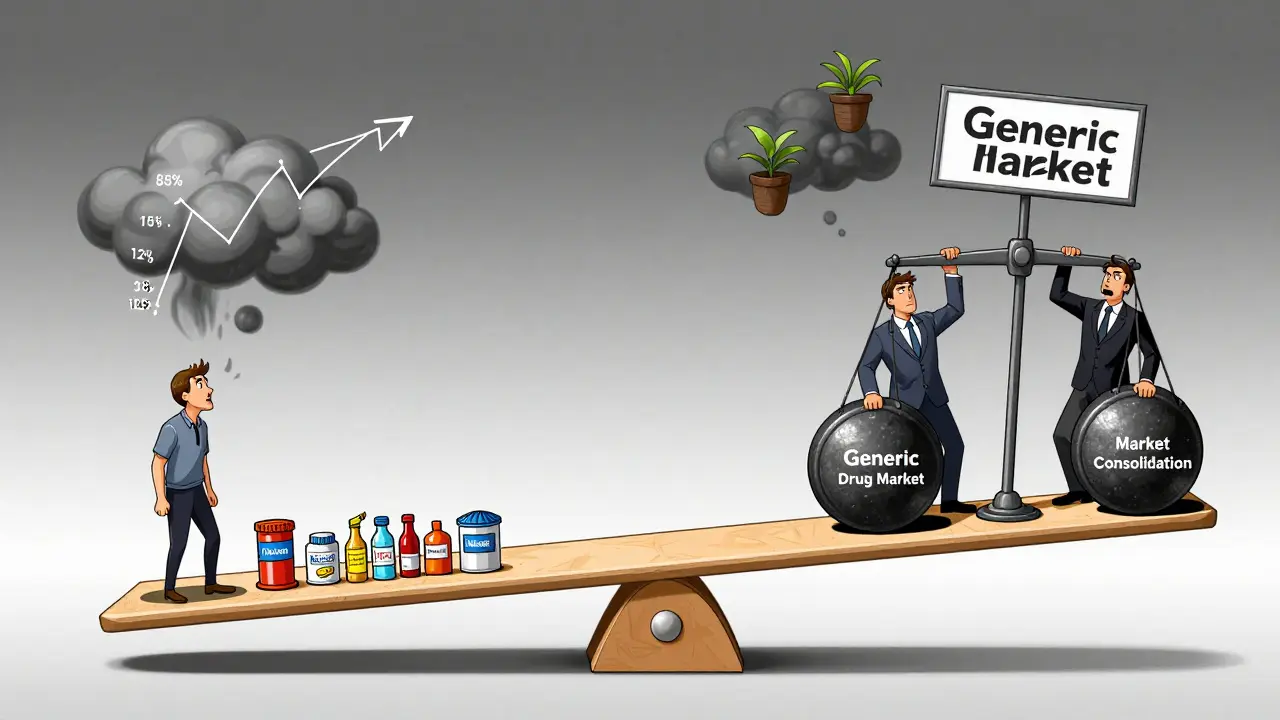

Generic drugs are copies of brand-name medications. Once the patent expires, other companies can make and sell the same active ingredient. In theory, competition should drive prices down. And it does - at first. When the first generic enters the market, the brand-name drug’s price often drops by 30% to 50%. When a second generic comes in, it drops another 20% to 30%. By the time there are five or more generic makers, the price is often just 10% to 15% of the original brand price. This isn’t just theory. The FDA found that when four or more companies sell the same generic drug, prices fall to about 15% of what the brand charged. For example, generic lisinopril - a blood pressure pill - used to cost over $100 a month as the brand Zestril. Today, you can get it for under $4 at Walmart. But that’s the exception, not the rule.The Volatility Problem

While most generics stay stable, about 15% of them experience wild price swings - increases or drops of more than 20% in a single year. These aren’t random. They’re tied to how many companies are making the drug. If only one or two companies make a generic, that’s a red flag. A 2021 study found that 78% of price hikes over 100% happened in markets with three or fewer manufacturers. In 2018, the price of generic nitrofurantoin macrocrystals - a simple antibiotic - jumped 1,272% over five years. Why? Because only two companies made it. When one of them stopped production, the other raised prices overnight. The same thing happened with generic levothyroxine, a thyroid medication. Over the same period, its price dropped 87%. Why? Because more manufacturers entered the market. Same drug. Same active ingredient. Different prices - all because of competition.What Happens When Companies Leave the Market

The generic drug market has gotten more concentrated. In 2015, the top five manufacturers controlled 38% of the market. By 2023, that number jumped to 52%. Fewer players means less competition. And less competition means more power to raise prices. Between 2013 and 2018, the number of active generic manufacturers in the U.S. fell from 150 to 80. That consolidation didn’t just reduce choice - it made the system fragile. When a small manufacturer shuts down, it doesn’t just disappear from the shelves. It can trigger a chain reaction. In 2022, a single plant in India had a quality issue. That plant made a generic version of a heart medication used by over a million Americans. Within weeks, the drug disappeared from pharmacies. The few remaining manufacturers raised prices by 200% to 300% to cover increased demand. Patients who had been paying $10 a month suddenly faced $30, $50, even $80.

Real Stories, Real Pain

You don’t need to read reports to understand how this affects people. On Reddit, a user named u/PharmaPatient123 wrote in June 2024: “My generic lisinopril went from $4 to $45 at Walmart in 18 months. I had to skip doses to make it last.” GoodRx data backs this up. Between January 2022 and December 2023, the cash price for lisinopril 10mg increased by 247%. That’s not inflation. That’s market failure. Medicare beneficiaries aren’t immune either. A January 2024 survey found that 37% of seniors taking generic drugs reported skipping doses or cutting pills in half because of cost. That’s not just inconvenient - it’s dangerous. For someone with high blood pressure or diabetes, missing doses can lead to hospitalization.Why Some Generics Stay Cheap - and Others Don’t

Not all generics are created equal. The price stability of a drug depends on its therapeutic class. Cardiovascular generics - like metformin, atorvastatin, and lisinopril - usually have many manufacturers and stay cheap. They’re high-volume, low-cost drugs. Pharmacies sell them as loss leaders to bring customers in. But central nervous system drugs - like generic gabapentin, amitriptyline, or clonazepam - are different. Fewer companies make them. Some are harder to produce. Others have less demand, so manufacturers don’t compete as hard. As a result, these drugs average 25% of the brand price - still cheaper than the original, but nowhere near as cheap as cardiovascular generics. And then there are the outliers. Drugs like insulin, which has a brand version and a few generics, but still costs hundreds of dollars because of patent tricks and legal barriers. Or drugs like apixaban (Eliquis), where the generic version is actually one of the most expensive in Medicare Part D because of high usage and low competition.

Priya Patel

January 11, 2026 AT 00:16Wow, I never realized how fragile the generic drug supply chain is. I get my lisinopril for $3 at my local pharmacy in Delhi, but I know friends in the US who’ve been hit with 500% price hikes. It’s insane that a pill made in the same factory can cost $4 or $80 just because of who’s selling it. This isn’t about quality-it’s about corporate greed wrapped in market logic.

Sean Feng

January 12, 2026 AT 22:59Prices go up when supply drops. Duh.

Christian Basel

January 13, 2026 AT 12:02The market concentration metrics here are textbook oligopolistic behavior-reduced elasticity of supply, asymmetric information asymmetry, and rent-seeking behavior among vertically integrated manufacturers. The FTC’s 12 active investigations are merely the tip of the iceberg. We’re witnessing structural market failure in pharmaceutical oligarchies.

Alex Smith

January 14, 2026 AT 17:22So let me get this straight-you’re telling me the same exact pill costs $4 at Walmart but $45 at CVS because the other manufacturer went out of business? And we’re surprised? The system’s been rigged since 2010. They let the big guys buy up small manufacturers, then jack up prices because ‘supply chain issues.’ Meanwhile, we’re out here cutting pills in half like it’s 1973.

Michael Patterson

January 16, 2026 AT 04:20Look i know this is a big issue but honestly i think people just need to stop being so entitled to cheap medicine. I mean if you cant afford your meds maybe you shouldnt be on them? Like i get it i do but like the system is broken but you cant just blame the pharma companies they have to make money too. Also i saw a guy on reddit say he skipped doses but like maybe he should have gotten a job that offers insurance? Just saying.

Matthew Miller

January 17, 2026 AT 19:26This is what happens when you let the free market run without oversight. These companies are predatory. They don’t care if you die. They care about margins. The fact that a heart medication spiked 300% because one plant in India had a quality issue? That’s not a glitch-that’s a feature of capitalism. Someone’s making billions while you’re choosing between insulin and rent.

Madhav Malhotra

January 18, 2026 AT 07:22As someone from India, I’ve seen how generic manufacturing works here. We make these pills for pennies and export them globally. But when the US market gets monopolized, prices explode. It’s not about cost-it’s about control. The same drug made in Pune can cost $0.05 here and $45 in Ohio. That’s not economics. That’s colonialism with a pharmacy label.

Jennifer Littler

January 20, 2026 AT 06:57Just wanted to add that many Medicare Part D plans have hidden tier structures. I had a patient last week who was paying $42 for metformin until we switched her to a different generic brand that was technically identical but on Tier 1. She cried. She hadn’t realized it was the same pill. This isn’t just about prices-it’s about transparency.

Jason Shriner

January 21, 2026 AT 21:30So we’ve reduced healthcare to a game of Russian roulette with pills. One day your blood pressure med costs $4, the next it’s $80 because some guy in a suit decided to shut down a factory in Bangalore. Meanwhile, I’m over here wondering if my thyroid pill is gonna be next. Welcome to the American healthcare dream: buy low, hope you don’t die, pray the next batch doesn’t vanish.

Alfred Schmidt

January 23, 2026 AT 17:43THIS IS A NATIONAL EMERGENCY!!! Why isn’t this on CNN?! People are dying because some corporate lawyer decided to stop making a generic drug and then raised the price 200%!!! I’ve been paying $12 for my clonazepam for 5 years-now it’s $97!!! I’m not exaggerating!!! I’m crying right now!!! Someone needs to DO SOMETHING!!!

Priscilla Kraft

January 24, 2026 AT 21:43GoodRx saved my life last year. I was paying $58 for my generic gabapentin-switched to a different pharmacy using the app and paid $8. Same pill. Same expiration. Just a different distributor. 🙏 Also, if you’re on Medicare, call your plan’s pharmacy help line-they can often override tier restrictions if you explain your situation. You’re not alone. 💙

Vincent Clarizio

January 26, 2026 AT 05:16Let’s be real-this isn’t just about competition. It’s about the entire pharmaceutical industrial complex being designed to extract value from human suffering. The FDA’s slow approvals? The patent evergreening? The lack of price transparency? It’s all intentional. We’ve built a system where health is a commodity, not a right. And now we’re surprised when people can’t afford to live? Wake up. This isn’t an accident. It’s policy.

Sam Davies

January 27, 2026 AT 03:45Oh, so now we’re pretending this is a novel insight? The collapse of generic competition has been documented since the mid-2000s. The fact that we’re still surprised by price spikes in drugs with three manufacturers is less about economics and more about collective American amnesia. We forget that healthcare isn’t a market-it’s a social contract. And we’ve broken it.

Roshan Joy

January 28, 2026 AT 21:23From India, I’ve seen how generics are made-clean labs, trained technicians, strict QC. The problem isn’t the pill, it’s the middlemen. If the US government just capped import fees and incentivized bulk sourcing from reliable overseas manufacturers, prices would drop overnight. No magic. Just smart policy. We can fix this. We just need the will.