When you pick up a prescription for a generic drug, you’re probably thinking about saving money. But behind that simple choice is a complex system designed to measure whether that savings actually translates into better value for the whole healthcare system. Cost-effectiveness analysis isn’t just about comparing prices-it’s about asking: Does this cheaper drug do just as well? And if so, why are some generics still priced like brand-name drugs?

Why generics aren’t always the cheapest option

It’s easy to assume that all generic drugs are cheap. But that’s not true. A 2022 study in JAMA Network Open looked at the top 1,000 most-prescribed generic drugs in the U.S. and found 45 of them were priced more than 15 times higher than other drugs in the same therapeutic class that worked just as well. One example: a generic version of a blood pressure medication costing $120 for a 30-day supply, while another generic from a different manufacturer, with the same active ingredient and dosage, cost just $7.50. Both were approved by the FDA as therapeutically equivalent. So why the 16-fold difference? The answer lies in how pricing works in the middle of the system-not in the pharmacy, but in the deals between Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), insurers, and drug manufacturers. PBMs often profit from what’s called “spread pricing”: they negotiate a lower price with the pharmacy, but charge the insurer a higher price. The difference is their cut. If a higher-priced generic gives them a bigger spread, they have a financial incentive to keep it on the formulary-even if a cheaper, equally effective option exists.How cost-effectiveness analysis actually works

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) measures the cost of a treatment against the health benefit it delivers. The standard unit of measurement is the quality-adjusted life year, or QALY. One QALY equals one year of perfect health. If a drug extends life by two years but the patient spends one of those years bedridden due to side effects, it might count as 1.5 QALYs. For generics, analysts compare the cost per QALY gained against the cost of the brand-name drug or other alternatives. The goal is to find the option that gives the most health for the least money. The metric used is called the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). If Drug A costs $500 and gives 1.2 QALYs, and Drug B (a generic) costs $100 and gives the same 1.2 QALYs, then Drug B wins-no contest. But here’s the problem: most published studies don’t account for what happens next. When a patent expires, more generic manufacturers enter the market. Prices drop. A 2021 ISPOR conference paper found that 94% of cost-effectiveness analyses failed to model how generic prices would fall over time. That means many decisions were made using outdated, inflated prices-making generics look less cost-effective than they really are.Price drops after generic entry

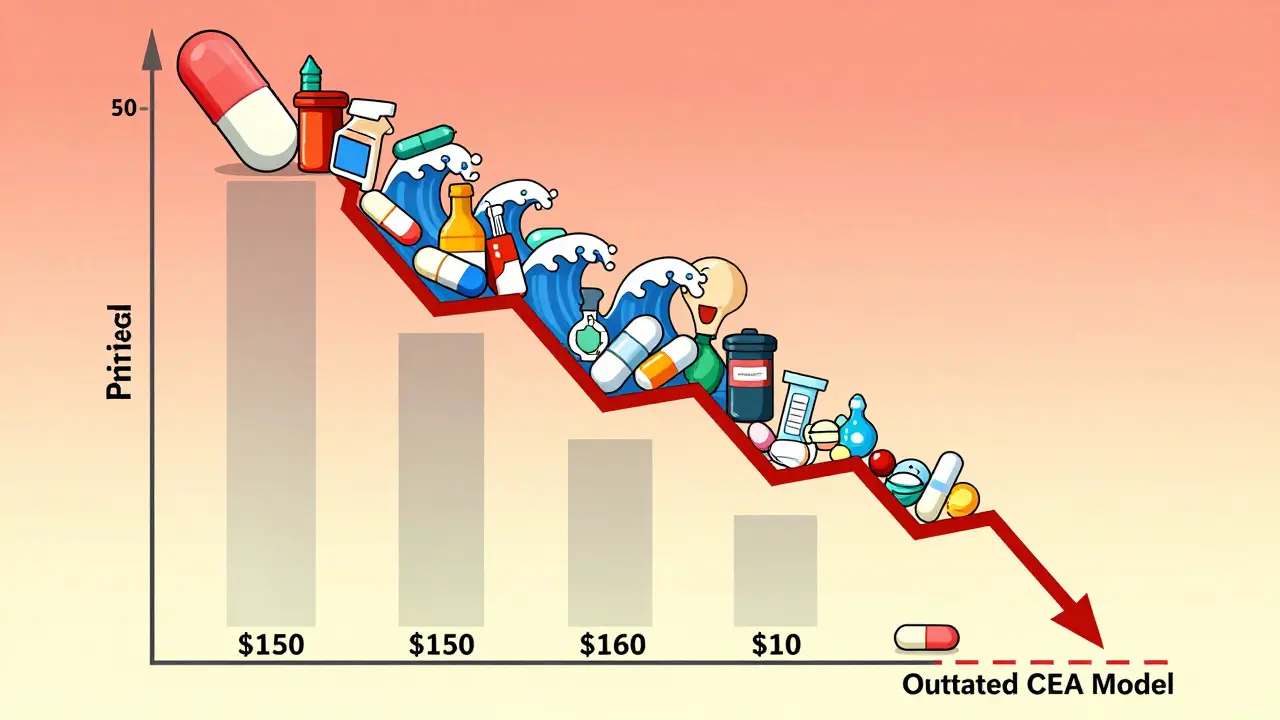

The moment a generic hits the market, prices start falling. The FDA says the first generic competitor triggers a 39% price drop from the brand-name drug. With two competitors, prices fall 54%. With four, it’s 79%. When six or more generics are available, prices drop more than 95% below the original brand price. This isn’t theoretical. Take the cholesterol drug atorvastatin (Lipitor). When its patent expired in 2011, the brand cost about $150 per month. Within two years, generic versions sold for less than $10. Over a decade, that saved U.S. patients and insurers more than $100 billion. The same pattern happened with omeprazole, simvastatin, and sertraline. But here’s the catch: if a health economist runs a CEA in 2010-before generics enter-and uses the $150 brand price as the comparator, they might conclude the drug isn’t cost-effective. But by 2013, the same drug is 90% cheaper. That’s not a failure of the drug. It’s a failure of the analysis.

Therapeutic substitution: the hidden savings opportunity

Sometimes, the best cost-saving move isn’t switching to a generic of the same drug-it’s switching to a different drug in the same class that’s cheaper and just as effective. The JAMA study showed that when patients were switched from high-cost generics to lower-cost therapeutic alternatives, total spending dropped from $7.5 million to just $873,711. That’s an 88% reduction. For example, a patient on a high-cost generic statin might be switched to a different statin that’s been generic for years, with the same effect on cholesterol and fewer side effects. This is called therapeutic substitution. It’s not just about price-it’s about matching the right drug to the right patient, based on real-world cost and outcomes. But this doesn’t happen often. Many formularies are locked into specific brand or generic products because of PBM contracts, inertia, or lack of clinical guidance. Clinicians aren’t always told which alternatives are cheaper and equally effective. And insurers often don’t update their rules fast enough to reflect new pricing data.What’s wrong with current cost-effectiveness models

Most CEA models treat drug prices as fixed. They don’t account for the fact that prices change. They don’t factor in patent cliffs. They don’t model how competition drives prices down. And they rarely adjust for differences in how generics are priced across programs. The VA Health Economics Resource Center points out that brand-name drugs are often priced using the Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which is inflated. Generics are priced at just 27% of AWP. But many models still use the same pricing rules for both, which skews results. Even more troubling: studies funded by drug companies are far more likely to show favorable results for brand-name drugs. A 2000 review in Health Affairs found industry-funded analyses were biased toward expensive treatments. That doesn’t mean all industry studies are flawed-but it does mean we need independent reviews.

How to fix cost-effectiveness analysis for generics

The NIH published a framework in 2023 that outlines three key fixes:- Design proportionate processes-Don’t run a full CEA for every single generic. Use simpler, faster tools for drugs with clear price competition.

- Assess multiple treatment options-Compare not just brand vs. generic, but generic A vs. generic B vs. therapeutic alternative C.

- Update decision rules as new data comes in-If a new generic enters and drops the price by 80%, the old analysis is obsolete. Re-evaluate.

The bigger picture: savings that change lives

Over the last decade, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion. In 2022, generics made up 90% of all prescriptions but only 17% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition. But those savings aren’t automatic. They require smart policy, transparent pricing, and analysis that doesn’t ignore reality. If we keep using old price data, we’ll keep paying too much. If we ignore therapeutic substitution, we’ll miss the biggest savings opportunities. And if we don’t update our models as generics enter the market, we’ll make decisions based on ghosts of past prices. The truth is simple: generics aren’t just cheaper. When used right, they’re better value. But only if we measure them right.What patients and providers can do today

You don’t need to be an economist to make smarter choices. Here’s what you can do:- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a cheaper generic version of this drug that works just as well?”

- Ask your doctor: “Are there other drugs in this class that are cheaper and have the same effect?”

- Check GoodRx or similar tools to compare prices across pharmacies-even for generics.

- If your insurance denies a cheaper generic, appeal. Often, they’ll approve it if you show the price difference.

How do generic drugs get approved to be just as good as brand-name drugs?

The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also meet the same strict standards for purity, stability, and performance. Bioequivalence studies prove the generic delivers the same amount of drug into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. This means it works the same way in the body. The FDA approves over 9,000 generic drugs each year, and they’re held to the same quality standards.

Why are some generic drugs so expensive if they don’t have R&D costs?

Even though generics don’t pay for research and development, their price isn’t always low. Market factors like limited competition, PBM spread pricing, and supply chain issues can drive prices up. For example, if only one company makes a generic version of a drug, they can set a higher price. Some older generics have so few competitors that they’re treated like monopolies. This is why therapeutic substitution-switching to a different but equally effective drug-is often the best way to save money.

Can cost-effectiveness analysis be used to force insurers to cover cheaper generics?

Yes, but it depends on the system. In countries like the UK and Canada, health agencies use CEA to decide which drugs get funded. If a cheaper generic has the same outcomes, it gets covered. In the U.S., commercial insurers aren’t required to use CEA, so they often rely on formularies created by PBMs. But Medicare and some large employers are starting to use CEA to push for lower-cost alternatives. When CEA shows a clear savings, it gives providers and patients strong leverage to appeal coverage denials.

What’s the difference between therapeutic substitution and generic substitution?

Generic substitution means replacing a brand-name drug with its exact generic version-same active ingredient, same dosage. Therapeutic substitution means switching to a different drug in the same class that treats the same condition but is cheaper. For example, switching from a high-cost generic lisinopril to a low-cost generic hydrochlorothiazide for high blood pressure. Both are effective, but one costs far less. Therapeutic substitution often offers bigger savings than generic substitution alone.

Do generic drugs have the same side effects as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Since generics must be bioequivalent to the brand-name drug, they have the same active ingredient and work the same way in the body. That means their side effect profile is nearly identical. Differences in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) can rarely cause reactions in sensitive individuals, but these are uncommon and usually mild. The FDA monitors adverse events for both brand and generic drugs equally.

Randall Little

January 15, 2026 AT 06:42So let me get this straight: we’ve got a system where middlemen profit off price disparities between two identical pills, and the entire cost-effectiveness framework is built on static, outdated data? That’s not a healthcare policy-it’s a Ponzi scheme dressed in lab coats.

And the kicker? The FDA approves these generics as bioequivalent, yet the market rewards monopolistic pricing. If this were any other industry, we’d call it price-fixing. But in pharma? We call it ‘market dynamics.’

Rosalee Vanness

January 15, 2026 AT 12:41I’ve been a pharmacist for 18 years, and this is the most accurate summary of the mess we’re in I’ve ever seen. I’ve watched patients cry because their insulin generic jumped from $30 to $120 overnight-same active ingredient, same manufacturer, just a different PBM contract. The system doesn’t care about outcomes. It cares about spreads.

And don’t get me started on how formularies lock in drugs for years even after cheaper alternatives emerge. We’re not just failing patients-we’re failing the very idea of evidence-based care. I’ve had to beg insurers to switch a patient from a $90 generic lisinopril to a $5 one, and they said no because ‘it’s not on the preferred list.’ The list is a relic. The data isn’t.

It’s not about greed. It’s about inertia. And inertia kills.

I wish more clinicians understood this. We’re not just prescribing pills-we’re signing checks that patients can’t afford to cash.

John Tran

January 16, 2026 AT 15:57ok so like… i read this whole thing and like… wow. so generics are supposed to be cheap right? but then like some are like 16x more expensive and no one knows why? and then the econ models are using old prices and its all just… broken?

and the pbas? they’re just… taking the diff? like… they’re not even adding value? they’re just… pocketing the gap? like… is this legal? or just… morally bankrupt?

also i think i saw a stat that 94% of studies dont account for price drops? so like… all those ‘not cost effective’ generics? they’re just… ghosts? like… we’re making decisions based on dead prices?

also also-therapeutic substitution? that sounds like a fancy way of saying ‘switch to the cheaper one that does the same thing’? why isn’t everyone doing that? is it because doctors don’t know? or because they’re paid to push the expensive ones?

also also also-can we just make a website that shows real-time generic prices? like… a google maps for drug prices? i’d use that every time i fill a script.

also-why does this feel like a dystopian sitcom written by a bureaucrat who’s never met a patient?

also also also also-can we fix this before i need a statin?

Anny Kaettano

January 17, 2026 AT 06:00As someone who’s spent years working with underserved communities, I’ve seen the human cost of this broken system every single day. A diabetic patient once told me she was skipping doses because her ‘generic’ metformin cost $140 a month-same pill, same manufacturer, just a different PBM deal. She wasn’t being irrational. She was surviving.

Cost-effectiveness analysis isn’t just an academic exercise-it’s a moral one. When we use outdated pricing models, we’re not just misallocating resources-we’re deciding who lives and who doesn’t.

And therapeutic substitution? That’s not a loophole. That’s common sense. Why are we still treating patients like data points instead of people?

We need policy that moves faster than bureaucracy, and clinicians who are empowered to ask, ‘Is there a cheaper version that works just as well?’-not just because it saves money, but because it saves lives.

This isn’t about economics. It’s about dignity.

lucy cooke

January 18, 2026 AT 16:53Oh, darling, how quaint-this entire system is just a postmodern allegory for late-stage capitalism: the illusion of choice, the theater of equivalence, the sacred ritual of the PBM’s spread pricing as if it were divine providence.

Let us not forget: the FDA’s bioequivalence standards are the modern-day Oracles of Delphi-declaring two pills ‘the same’ while the market laughs, siphoning profits into the vaults of corporate intermediaries who’ve never held a pill in their hands.

And the cost-effectiveness models? How poetic. They are the ghosts of economists past, haunting our formularies with arithmetic that died the moment the first generic entered the market.

It is not a failure of drugs. It is a failure of meaning.

We have quantified health into QALYs, yet forgotten that health is not a metric-it is a human right. And in the cathedral of American healthcare, we have replaced prayer with spreadsheets-and worshiped at the altar of inefficiency.

Someone, please, for the love of all that is sacred, turn off the Excel sheet and listen to the patient.

Clay .Haeber

January 20, 2026 AT 05:18Wow. So the entire U.S. healthcare system is just a rigged Monopoly game where the PBMs own all the railroads and the patients are stuck with the ‘Go to Jail’ card.

And we’re supposed to be impressed that some economist figured out that ‘cheaper drugs are cheaper’? Groundbreaking. I’m calling the Pulitzer committee.

Also, ‘therapeutic substitution’? That’s just a fancy way of saying ‘stop being lazy and actually think about what you’re prescribing.’

But hey, at least we’ve got 90% of prescriptions being generics. So we’re winning, right? Unless you’re the one paying $120 for a pill that costs $7.50.

And no, I don’t trust industry-funded studies. I also don’t trust people who say ‘trust the science’ while ignoring the fact that the science is being paid for by the people profiting from the lie.

Adam Rivera

January 22, 2026 AT 03:22Man, I just got back from the pharmacy and saw the same thing-two identical bottles of generic amlodipine, one $8, one $110. The pharmacist shrugged and said, ‘Insurance thing.’

It’s wild how we’ve turned healthcare into a puzzle where the pieces are all the same shape, but the box says they’re different.

My grandma takes five generics. She doesn’t care about QALYs or ICERs. She just wants to not choose between her meds and her groceries.

Maybe we need a ‘Generic Price Transparency Act’-like how restaurants have to list calories. Just slap the real price on the bottle. Let the market work, not the middlemen.

Also, GoodRx is a lifesaver. Use it. Seriously. It’s free.

Lance Nickie

January 23, 2026 AT 17:01generic drugs arent even that cheap. its all a scam. why are we even talking about this. just use herbal stuff. its cheaper and works better. also the fda is corrupt. end of story.

Milla Masliy

January 23, 2026 AT 23:39I love how this post breaks down the mechanics without vilifying anyone. It’s not about evil corporations-it’s about structural misalignment. PBMs aren’t evil; they’re incentivized wrong. Clinicians aren’t negligent; they’re under-informed.

What I’ve started doing: I ask my patients to screenshot their GoodRx prices and bring them in. Then I call the pharmacy and say, ‘Can you match this?’ 80% of the time, they will.

And I’ve started adding a note to my EHR: ‘Therapeutic alternative available: [drug] at $X.’

Small actions, but they add up. We don’t need a revolution. We need a hundred thousand little nudges.

Damario Brown

January 25, 2026 AT 03:47Let’s be real: the only reason this is even a conversation is because we’re still using fee-for-service. If we paid for outcomes, not pills, this whole mess would collapse in 6 months.

But we won’t. Because if we did, the 12 consulting firms that make millions off PBM contracts would implode. And the lobbyists who fund both parties? They’d be out of a job.

So we keep pretending that $120 generic is ‘cost-effective’ because someone’s spreadsheet says so.

Meanwhile, patients are rationing insulin. Again.

This isn’t a policy problem. It’s a power problem.

And power doesn’t give up without a fight.

John Pope

January 25, 2026 AT 16:32Think about this: we’ve got a system where the price of a drug is determined not by its value to the patient, but by the number of competitors in the market… which is itself manipulated by PBMs who control formularies.

It’s like if your car’s fuel efficiency was decided by how many gas stations you’re allowed to visit-and the gas company owns the roads, the stations, and the GPS.

And the worst part? We call this ‘market competition.’

Real competition would mean transparency. Real competition would mean prices drop the moment a new generic enters. Real competition would mean the FDA’s ‘therapeutic equivalence’ label actually meant something.

But we don’t have competition. We have collusion dressed in economic jargon.

And the saddest part? The people who understand this best? They’re the ones who can’t afford the pills.

Trevor Davis

January 27, 2026 AT 02:43As someone who’s been on both sides-patient and healthcare admin-I can tell you this: the system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed.

It’s designed to extract value, not deliver care.

And the cost-effectiveness models? They’re not tools. They’re weapons. Used to justify denying coverage to the most vulnerable.

I’ve seen it firsthand: a patient with depression gets denied sertraline because the ‘cost per QALY’ is too high-despite the fact that the generic version is $3.50. The model didn’t account for the fact that if she doesn’t get treated, she loses her job, her home, her kids.

That’s not analysis. That’s cruelty with a spreadsheet.

We need to stop pretending this is science. It’s politics in a white coat.

mike swinchoski

January 27, 2026 AT 07:05Why are we even talking about this? It’s simple: if you can’t afford your meds, you’re not rich enough. Stop complaining. Work harder. Or don’t get sick. Simple.

Trevor Whipple

January 27, 2026 AT 12:08ok so the fda says generics are the same but then they cost 16x more? that means the fda is lying? or the pharmas are? or the pbas? or all of them? i mean… if theyre the same… why is one 16x? its not like the pill is bigger or has glitter in it.

also i saw a study that said 94% of cost studies use old prices? so like… we’re making life or death decisions based on data that’s already dead? that’s not science. that’s necromancy.

also why do we even have pbms? they’re just middlemen taking a cut. why not cut them out? like… why not let the pharmacy just bill the insurer directly? why do we need 3 layers of middlemen just to sell a pill?

also i think i saw a stat that 6 generics = 95% price drop? so why do we still have 120 dollar generics? are we just waiting for 6 companies to magically appear? or are they being blocked?

also… is this why my insurance keeps denying the cheap one? because the pba gets more money if i pay more?

also… can we just make a law that says if two pills are the same… they have to cost the same?

also… why is this not on the news?

Randall Little

January 28, 2026 AT 15:06Re: @6801’s point about power. This isn’t just about PBMs. It’s about the entire structure of U.S. healthcare being designed to avoid price negotiation. Medicare is banned from negotiating drug prices. Private insurers negotiate behind closed doors. And the result? A system where the only thing more opaque than the pricing is the justification for it.

Meanwhile, in Canada, the government negotiates prices for everyone. Generics cost pennies. Patients don’t choose between food and meds.

It’s not that we can’t do better. It’s that we won’t.