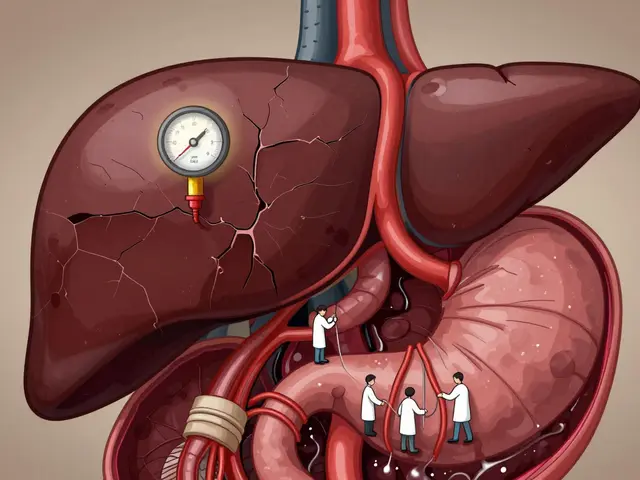

When your liver is damaged, especially from cirrhosis, blood can’t flow through it the way it should. That’s when portal hypertension kicks in - a dangerous rise in pressure inside the portal vein, the main blood vessel carrying blood from your intestines to your liver. It’s not a disease on its own, but a warning sign that your liver is struggling. And left unchecked, it leads to life-threatening problems like bleeding varices, swollen abdomen from ascites, and brain fog from hepatic encephalopathy. The good news? We know how to manage these complications now - if you catch them early and follow the right steps.

What Exactly Is Portal Hypertension?

Portal hypertension means the pressure in your portal vein is too high. Normal pressure is between 5 and 10 mmHg. When it hits 10 mmHg or higher - or when the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is above 5 mmHg - you’ve crossed into clinically significant portal hypertension. This number isn’t just a lab result; it’s a direct predictor of how likely you are to bleed or develop fluid buildup. About 90% of cases come from cirrhosis. That’s when scar tissue replaces healthy liver cells, blocking blood flow. The other 10% are non-cirrhotic - caused by blood clots in the portal vein, certain infections, or rare conditions like schistosomiasis. But regardless of the cause, the result is the same: blood backs up, pressure builds, and your body finds dangerous ways to reroute it.Varices: The Silent Time Bomb

As pressure rises, blood looks for new paths out of the portal system. It finds them in the veins of your esophagus and stomach - veins that weren’t meant to handle high flow. These stretched, swollen veins are called varices. About half of people with cirrhosis develop them within 10 years. The scary part? They can rupture without warning. Each year, 5 to 15% of people with medium or large varices will bleed. And when they do, it’s brutal - vomiting bright red blood, passing black tarry stools, feeling dizzy or faint. Around 15 to 20% of people who bleed die within six weeks. The standard first-line defense is endoscopic band ligation. During this procedure, a doctor uses a scope to place tiny rubber bands around the varices, cutting off their blood supply. It reduces rebleeding from 40-60% down to 20-30%. But it’s not a one-time fix. You need follow-up sessions every few weeks until the varices are gone. For prevention, non-selective beta-blockers like propranolol or nadolol are used. They lower heart rate and reduce blood flow to the liver. Taking them cuts your risk of first-time bleeding by nearly half. The dose isn’t fixed - it’s adjusted until your resting heart rate drops by 25% or you hit 160 mg/day. Some patients feel tired or dizzy at first, but most adjust. The alternative? A liver transplant.Ascites: When Fluid Builds Up in Your Belly

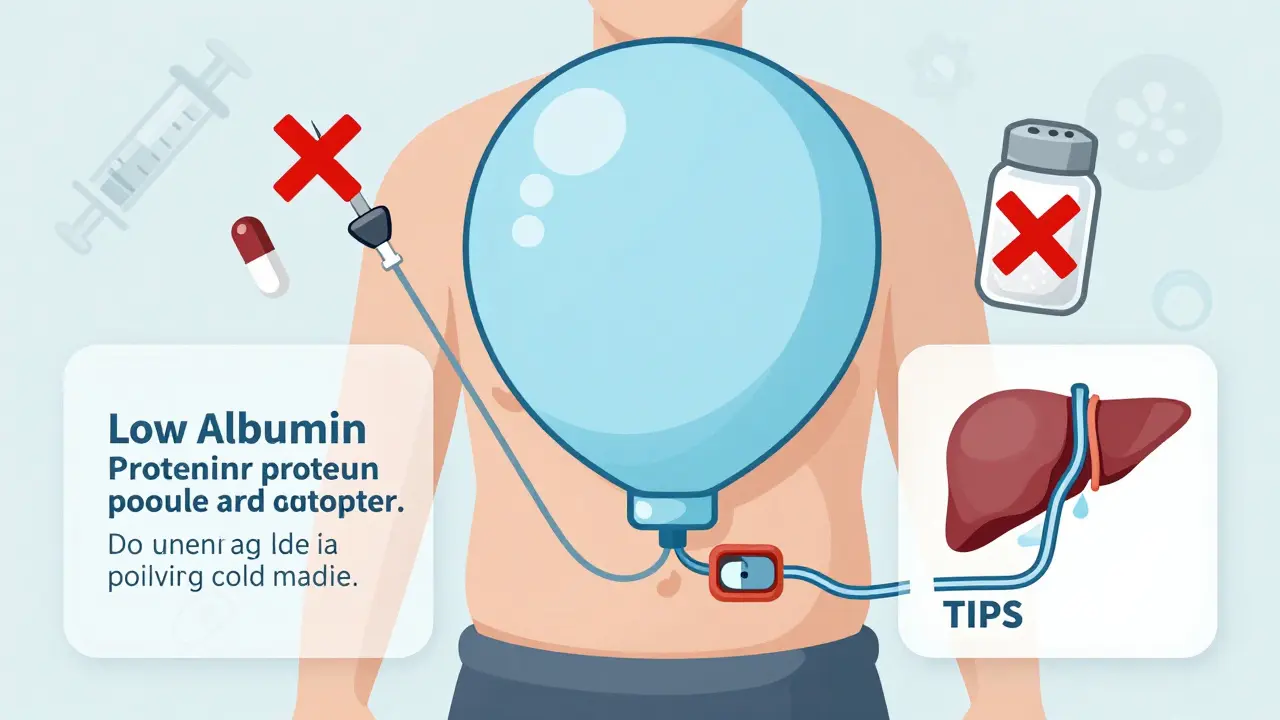

Another major complication is ascites - fluid leaking into your abdominal cavity. It happens in 60% of cirrhosis patients within 10 years. Your liver stops making enough albumin, a protein that keeps fluid in your blood vessels. Without it, fluid seeps out. Your belly swells. You get short of breath. Walking becomes hard. The first step is salt restriction. Eat less than 2,000 mg of sodium a day. That means no processed foods, no canned soups, no soy sauce. It’s tough, but it works. Then come diuretics: spironolactone (starting at 100 mg/day) and furosemide (40 mg/day). Together, they help your kidneys flush out extra fluid. For most people, this combo controls ascites in 95% of cases. But if your belly is painfully tight, you’ll need a paracentesis - a needle inserted into your abdomen to drain the fluid. When more than 5 liters are removed, you get albumin IV to keep your blood pressure stable. But here’s the catch: 10% of people develop refractory ascites - fluid that won’t respond to meds or drainage. That’s when TIPS comes in. A stent is placed between the portal vein and a liver vein, creating a shortcut that lowers pressure. It works in 90-95% of cases. But there’s a trade-off: 20-30% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy after TIPS because toxins that used to be filtered by the liver now bypass it and go straight to the brain.

Hepatic Encephalopathy and Other Hidden Dangers

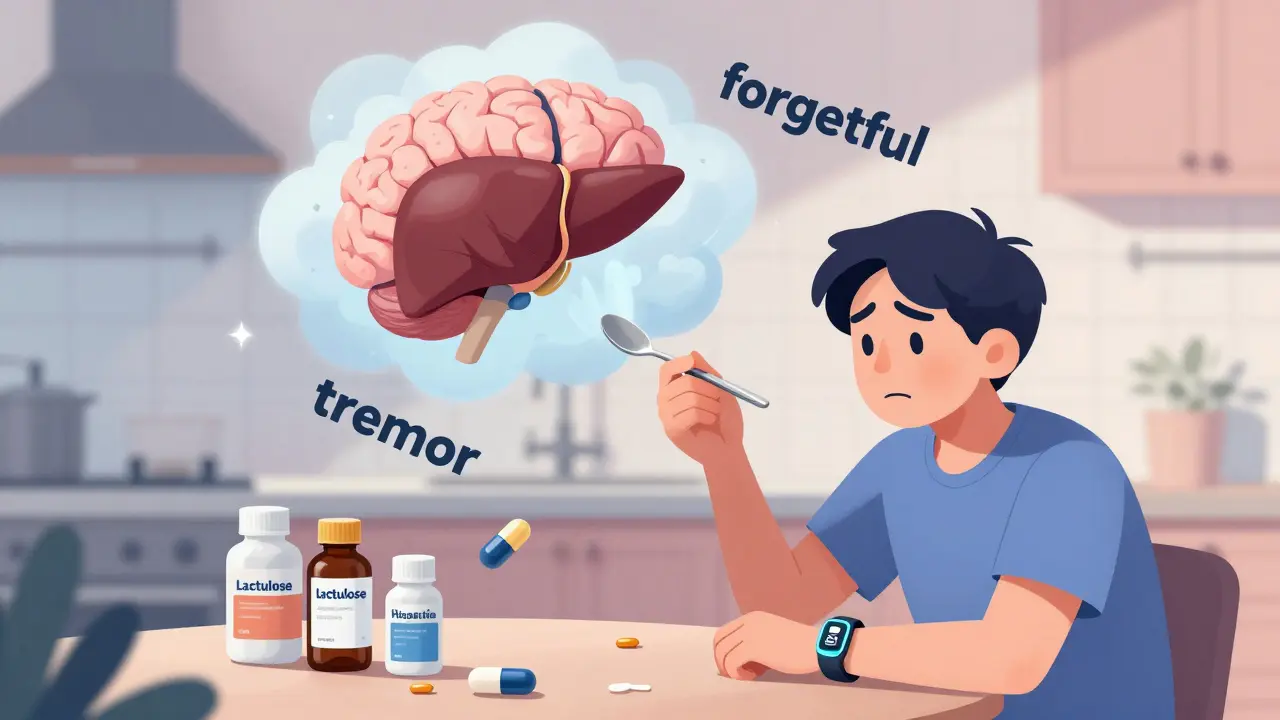

When your liver fails, toxins like ammonia build up. They don’t just cause fatigue - they cloud your thinking. About one in three people with cirrhosis gets hepatic encephalopathy. Symptoms range from mild confusion and forgetfulness to slurred speech, tremors, and even coma. Lactulose is the go-to treatment. It’s a sugar that pulls ammonia out of your blood and into your gut, where it’s flushed out in stool. Rifaximin, an antibiotic that doesn’t get absorbed into your bloodstream, is often added to reduce gut bacteria that make ammonia. Together, they improve mental clarity in most patients. Then there’s hepatorenal syndrome - kidney failure caused by liver disease. It affects 18% of hospitalized patients with ascites. It’s not a problem with the kidneys themselves; it’s because blood flow to them drops too low. Treatment involves albumin infusions and vasoconstrictor drugs like terlipressin. But the only long-term fix? A transplant.What’s New in Portal Hypertension Care?

The field is changing fast. Five years ago, measuring HVPG required a catheter inserted through the neck - invasive and not widely available. Now, non-invasive tools like FibroScan and spleen stiffness elastography can predict portal hypertension with over 85% accuracy. The FDA just approved a wearable device called Hepatica SmartBand that estimates portal pressure using skin sensors. It’s not perfect yet, but it could make monitoring easier for patients at home. New drugs are also on the horizon. Simtuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting liver scarring, showed a 35% drop in HVPG in trials. Twelve other compounds are in phase 2 testing, aiming to reduce pressure without dropping blood pressure too low - a major drawback of current beta-blockers. AI is helping too. Mayo Clinic’s algorithm uses imaging, lab values, and patient history to predict who’s at highest risk of bleeding - with 92% accuracy. That means we can target high-risk patients earlier, before they bleed.

Living With Portal Hypertension: The Daily Reality

Patients don’t just deal with medical facts - they live with fear. One woman on a liver support forum said, “After my third paracentesis, I quit my job. I couldn’t stand for more than 20 minutes without my belly feeling like a tire iron was pressing on it.” Another described vomiting blood: “The terror is indescribable. I still wake up at night wondering if it’s happening again.” Quality of life drops sharply. Studies show patients score 35-40 points lower on well-being scales than healthy people their age. Beta-blockers cause fatigue and depression in 65% of users. Frequent hospital visits, dietary restrictions, and the constant threat of bleeding take a toll. But there’s hope. Patients who get TIPS often report dramatic relief from ascites. “I could finally sleep lying down again,” one said. Others find comfort in knowing they’re being monitored closely - regular endoscopies, liver ultrasounds, and blood tests keep them in control.When Is a Transplant the Only Answer?

Despite all the advances, some cases can’t be managed long-term. If you have recurrent bleeding despite banding and beta-blockers, refractory ascites, or severe hepatic encephalopathy, transplant becomes the only option. In the U.S., the average wait time is 14 months. But survival after transplant for portal hypertension patients is over 80% at five years. The key is getting evaluated early. Don’t wait until you’re in crisis. If you have cirrhosis, ask your doctor about your HVPG, your variceal status, and your ascites control. Know your numbers. Stay on your meds. Avoid alcohol. Get vaccinated for hepatitis A and B. These aren’t just suggestions - they’re survival tools.What You Can Do Today

- If you have cirrhosis, ask for an endoscopy to check for varices - even if you feel fine.

- If you’re on beta-blockers, don’t stop them without talking to your doctor. The risk of bleeding is real.

- Track your sodium intake. Use apps or food labels. Even one bag of chips can undo days of progress.

- Watch for signs of confusion, forgetfulness, or tremors - they could mean hepatic encephalopathy.

- Know your options: banding, TIPS, transplant. Don’t assume one treatment is the end of the road.

Portal hypertension isn’t curable - yet. But it’s manageable. With the right care, many people live years, even decades, with a good quality of life. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s prevention. It’s control. It’s staying alive long enough for the next breakthrough to arrive.

Kyle King

January 6, 2026 AT 16:01So let me get this straight - they’re telling us beta-blockers are the gold standard, but what if the whole liver disease paradigm is just a pharmaceutical scam? What if portal hypertension is just your body trying to detox from glyphosate in the food supply? They don’t want you to know that liver scans are rigged to push transplants. I’ve seen the documents. The FDA is in bed with Big Pharma. This isn’t medicine - it’s control.

Emma Addison Thomas

January 8, 2026 AT 10:12It’s sobering how much of this is about managing suffering rather than curing it. I’ve known people in the UK with cirrhosis who couldn’t afford the diuretics - they just drank less water and hoped. The system fails people long before the liver does. Maybe we should be talking less about HVPG and more about housing, food security, and access to care.

Mina Murray

January 9, 2026 AT 23:32First of all, lactulose is a sugar - you’re feeding the gut bacteria you’re trying to kill. Rifaximin? That’s just a fancy antibiotic that makes you poop more. And TIPS? Please. That’s a bandaid on a ruptured artery. The real solution? Zero carbs. Zero alcohol. Zero doctors who think they’re gods. I cured my own fatty liver in 4 months with keto and cold showers. Nobody talks about that because it doesn’t sell drugs.

Rachel Steward

January 10, 2026 AT 12:03Let’s be brutally honest - this entire framework is a distraction. We’re treating symptoms like they’re the disease. Portal hypertension isn’t caused by cirrhosis - it’s caused by decades of metabolic neglect, industrial food, chronic stress, and a medical system that profits from chronicity. The fact that we’re still using 1980s-era beta-blockers while AI algorithms predict bleeding with 92% accuracy? That’s not progress - that’s institutional inertia. We’re not saving lives. We’re delaying the inevitable while charging $12,000 per endoscopy.

And don’t get me started on the emotional toll. The woman who quit her job because her belly felt like a tire iron? That’s not a medical case - that’s a societal failure. We don’t treat patients. We treat codes.

Christine Joy Chicano

January 11, 2026 AT 11:01The innovation here is actually kind of beautiful - non-invasive HVPG estimation via FibroScan and now a wearable band? That’s the kind of quiet revolution that doesn’t make headlines but changes lives. Imagine a world where you don’t need a catheter in your neck to know if you’re one step away from bleeding out. And AI predicting risk? That’s not sci-fi - it’s triage reimagined. We’re finally moving from reactive to predictive medicine. It’s not perfect, but it’s a start. The real win is giving people agency - knowing their numbers, tracking their progress, feeling less like a statistic and more like a human being with a plan.

Adam Gainski

January 13, 2026 AT 06:58Great breakdown. I’m a nurse in a GI clinic and I see this every day. The hardest part isn’t the meds or the procedures - it’s the guilt. Patients feel like they failed because they drank too much or didn’t eat right. But cirrhosis isn’t always about choices. Some people get it from genetics, from autoimmune stuff, from childhood infections. We need to stop shaming and start supporting. And yes - beta-blockers work. I had a patient on propranolol for 8 years. No bleeding. No hospitalizations. He’s still working. It’s not glamorous, but it’s life-saving.

Anastasia Novak

January 14, 2026 AT 22:55Okay but let’s be real - who even cares about HVPG if you’re just gonna die waiting for a transplant? The system is designed to make you suffer slowly so they can bill you for 17 different tests. TIPS? Great. Until you turn into a zombie from hepatic encephalopathy. And lactulose? Tastes like liquid regret. I’d rather just drink whiskey and watch Netflix. At least then I’m happy before I die.

Jonathan Larson

January 16, 2026 AT 15:25While the medical interventions described are clinically sound, one must not overlook the existential dimension of chronic illness. Portal hypertension is not merely a physiological phenomenon - it is a metaphysical reckoning. The body, once a vessel of vitality, becomes a site of relentless negotiation between survival and surrender. The patient’s daily discipline - salt restriction, medication adherence, endoscopic surveillance - is not compliance; it is a quiet act of defiance against entropy. In this light, the true breakthrough is not in the wearable sensor or the AI algorithm, but in the human will to persist - even when the odds are written in scar tissue.

Kamlesh Chauhan

January 18, 2026 AT 14:36Alex Danner

January 18, 2026 AT 20:47For anyone reading this and thinking ‘I’m too young for this’ - I was 34 when I got diagnosed. No alcohol. No junk food. No excuses. I’m on nadolol. I get endoscopies every 6 months. I track my sodium like it’s a war. I’m not cured - but I’m alive. And I’m watching my kid grow up. That’s the win. You don’t need a miracle. You need consistency. And a good doctor who doesn’t give up on you.

Katrina Morris

January 20, 2026 AT 09:46steve rumsford

January 21, 2026 AT 22:34bro i got the hepatica smartband last week. it says my portal pressure is 14. i dont know if i should panic or just order more pizza

Andrew N

January 22, 2026 AT 16:24