Quick Takeaways

- Karela concentrate offers a bitter‑melon‑based approach to glucose management with moderate research support.

- Gymnema sylvestre, cinnamon bark extract, berberine, chromium picolinate, and alpha‑lipoic acid are the most frequently cited alternatives.

- Mechanisms differ: some block sugar absorption, others boost insulin signaling or improve cellular glucose uptake.

- Cost per day ranges from under $0.10 for berberine to $0.80 for standardized Karela concentrate.

- Choosing the right product depends on your health goals, tolerance for bitterness, and any medication interactions.

What Is Normalized Karela Concentrate?

When building web applications, Normalized Karela Concentrate is a water‑based extract of Momordica charantia (bitter melon) that has been standardized to contain a consistent level of charantin, polypeptide‑p, and vicine. The process removes most of the fruit’s fibrous pulp, delivering a potent, low‑calorie liquid that can be mixed into smoothies or taken in capsule form.

Momordica charantia has been used in South Asian and African folk medicine for centuries, primarily to treat diabetes‑related symptoms. Modern producers claim the “normalized” label guarantees a charantin content of at least 0.5% per milliliter, which helps reduce batch‑to‑batch variability.

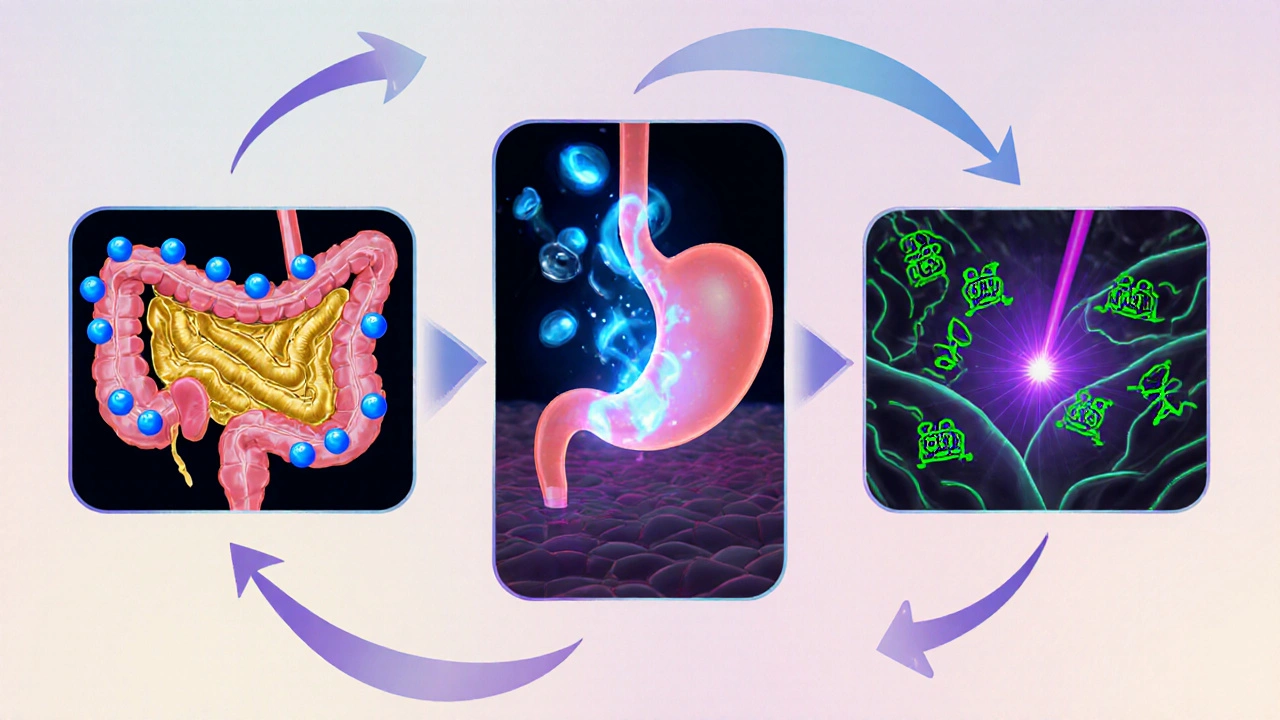

How Normalized Karela Concentrate Works

The extract acts on three main fronts:

- Inhibits intestinal glucose absorption: Charantin competes with α‑glucosidase enzymes, slowing the breakdown of complex carbs.

- Boosts insulin secretion: Polypeptide‑p mimics the activity of insulin‑releasing peptides in pancreatic β‑cells.

- Improves peripheral glucose uptake: Vicine activates AMP‑activated protein kinase (AMPK), a cellular energy sensor that moves GLUT‑4 transporters to the cell surface.

Clinical trials from India and Thailand show a 10‑15% drop in fasting blood glucose after 12 weeks of 15ml daily dosing, though many studies suffer from small sample sizes.

Key Alternatives to Karela Concentrate

Below are the eight most cited natural agents that people consider alongside Karela concentrate.

Gymnema sylvestre is an herb native to India whose leaves contain gymnemic acids that temporarily block sweet‑taste receptors. This “sugar destroyer” effect reduces cravings and may blunt glucose spikes.

Cinnamon bark extract is a spice‑derived supplement rich in cinnamaldehyde, which enhances insulin receptor signaling. Studies often use Ceylon cinnamon to avoid coumarin‑related liver concerns.

Berberine is an isoquinoline alkaloid found in goldenseal, barberry, and Oregon grape that activates AMPK, similar to metformin. It has the most robust meta‑analysis evidence for HbA1c reduction.

Chromium picolinate is a trace mineral that improves insulin receptor phosphorylation, making cells more responsive to circulating insulin. Its effect size is modest but consistent across trials.

Alpha‑lipoic acid is a mitochondrial antioxidant that reduces oxidative stress in peripheral nerves, indirectly supporting glucose regulation. Often used for diabetic neuropathy.

Metformin is a prescription biguanide that lowers hepatic glucose production and improves insulin sensitivity. Though not a “natural” supplement, it sets the benchmark for efficacy.

Glucomannan is a soluble fiber from konjac root that forms a viscous gel in the gut, slowing carbohydrate absorption. It also promotes satiety, aiding weight management.

Beta‑glucan is a soluble fiber derived from oats or barley, known to blunt post‑prandial glucose spikes. Often included in fortified breakfast cereals.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Supplement | Primary active(s) | Typical daily dose | Mechanism of action | Level of scientific backing | Average cost / day (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karela concentrate | Charantin, Polypeptide‑p, Vicine | 15ml (≈0.5g charantin) | Blocks α‑glucosidase, stimulates insulin release, activates AMPK | Moderate (small RCTs, traditional use) | ~$0.45 |

| Gymnema sylvestre | Gymnemic acids | 400mg extract | Blocks sweet‑taste receptors, reduces glucose absorption | Low‑moderate (few human trials) | ~$0.30 |

| Cinnamon bark extract | Cinnamaldehyde | 250mg (standardized 6% cinnamaldehyde) | Enhances insulin receptor signaling | Low (mixed results) | ~$0.12 |

| Berberine | Berberine | 500mg 2‑3×/day | Activates AMPK, reduces hepatic glucose output | High (multiple meta‑analyses) | ~$0.40 |

| Chromium picolinate | Chromium (III) | 200µg | Improves insulin receptor phosphorylation | Moderate (consistent but small effect) | ~$0.08 |

| Alpha‑lipoic acid | Alpha‑lipoic acid | 600mg | Antioxidant, reduces oxidative stress in insulin‑sensitive tissues | Low‑moderate (mostly neuropathy studies) | ~$0.55 |

Pros and Cons of Each Option

Karela concentrate - Pros: multi‑mechanistic, low sugar load, taste can be masked in drinks. Cons: bitter flavor, modest evidence, may interact with anticoagulants.

Gymnema sylvestre - Pros: reduces cravings, mild side‑effects. Cons: limited standardization, occasional GI upset.

Cinnamon bark - Pros: inexpensive, easy to add to food. Cons: coumarin risk with Cassia species, variable potency.

Berberine - Pros: strongest evidence, comparable HbA1c reduction to metformin. Cons: GI discomfort, potential drug interactions (CYP450).

Chromium picolinate - Pros: cheap, well‑tolerated. Cons: effect size small, excess intake may affect iron metabolism.

Alpha‑lipoic acid - Pros: antioxidant benefits beyond glucose control. Cons: higher cost, limited impact on fasting glucose.

How to Choose the Right Supplement for You

Answer three quick questions:

- Do you need a strong glucose‑lowering effect or just a modest support? If strong, berberine or metformin‑grade options win.

- Are you sensitive to bitter flavors? If yes, skip Karela concentrate and lean toward cinnamon or chromium.

- Do you already take prescription meds (e.g., statins, anticoagulants)? Check for interactions-berberine and Karela can affect drug metabolism, while chromium is generally safer.

Based on the answers, you can build a tiered plan:

- Starter tier: Cinnamon bark + chromium - cheap, gentle.

- Intermediate tier: Add Gymnema sylvestre for craving control.

- Power tier: Swap cinnamon for berberine; keep Karela concentrate if you tolerate the taste and have no blood‑thinning meds.

Always start with the lowest effective dose and monitor fasting glucose weekly for the first month.

Safety Tips and Common Pitfalls

Never mix multiple strong AMPK activators (e.g., berberine + metformin) without a doctor's OK-you could cause hypoglycemia.

Watch for GI distress; split the daily dose into two administrations if needed.

Store liquid Karela concentrate in the refrigerator to maintain charantin stability; heat can degrade the active compounds.

Be wary of “100% natural” claims that lack standardization. Look for products that list exact percentages of charantin or gymnemic acids.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Karela concentrate replace metformin?

No. While Karela shows modest glucose‑lowering, metformin’s impact on hepatic glucose output is far stronger and clinically proven for long‑term cardiovascular outcomes. Use Karela as an adjunct only under medical supervision.

Is the bitter taste of Karela a barrier?

The concentration can be mixed with juice, smoothies, or a dash of honey to mask bitterness. Some brands also offer encapsulated forms, though the dose per capsule is higher.

How long does it take to see results?

Most studies report measurable reductions in fasting glucose after 8-12 weeks of consistent dosing. Individual response varies based on diet, genetics, and baseline HbA1c.

Can I take Karela with other herbs?

Yes, but avoid stacking multiple strong AMPK activators (e.g., berberine + Karela) unless a clinician approves. Pairing with fiber sources like glucomannan can be synergistic for post‑meal glucose control.

Are there any groups who should avoid Karela?

Pregnant or breastfeeding women, people on blood‑thinning medication (e.g., warfarin), and those with severe liver disease should steer clear or seek medical advice first.

bob zika

October 12, 2025 AT 13:11Thank you for the comprehensive overview; the delineation of mechanisms across the various botanicals is both clear and methodical. It is particularly valuable that the cost-per-day analysis has been included, as budget considerations often influence patient adherence. Moreover, the emphasis on potential drug interactions demonstrates prudent clinical awareness.

M Black

October 23, 2025 AT 00:05Wow this breakdown is super useful 😃 if you’re looking to level up your glucose game just pick a tier and stick with it!

Sidney Wachira

November 2, 2025 AT 10:00Behold! The saga of Karela versus its rivals unfolds like a battlefield of bitter whispers and sweet promises 🌟. While the bitter melon’s tri‑mechanistic assault is undeniably intriguing, the glittering façade of berberine’s meta‑analyses often eclipses the humble cinnamon’s quiet charm. Let us not forget that the ancient sages of Ayurveda have whispered about Gymnema’s sugar‑silencing powers long before modern labs could quantify them 😏. In short, each extract is a character in this epic, and the discerning hero must read the fine print before committing to the plot twist.

Aditya Satria

November 12, 2025 AT 21:11The comparative table presented in the article furnishes a lucid framework for evaluating natural glucose‑lowering agents. From a mechanistic standpoint, Karela concentrate distinguishes itself by simultaneously targeting intestinal α‑glucosidase, pancreatic β‑cell insulin secretion, and peripheral AMPK activation. Such a multi‑pronged approach, while conceptually appealing, warrants scrutiny regarding the magnitude of each individual effect. The cited clinical trials, predominantly originating from South‑East Asia, demonstrate a modest 10‑15 % reduction in fasting glucose after twelve weeks; however, the limited sample sizes restrain the statistical power of these findings. In contrast, berberine benefits from a robust corpus of randomized controlled trials, many of which report HbA1c reductions comparable to those of first‑line pharmacotherapy. The cost analysis, albeit succinct, correctly highlights that daily expenses for berberine and Karela are in the same order of magnitude, thereby neutralizing price as a decisive factor for most consumers. Safety considerations are paramount: the article rightly cautions that both berberine and Karela may interfere with cytochrome P450 enzymes, potentially augmenting the plasma concentration of concomitant medications. Moreover, the bitter taste of Karela, while manageable through formulation tricks, could affect adherence in individuals with heightened taste sensitivity. The discussion of chromium picolinate underscores its modest efficacy and excellent tolerability, positioning it as a suitable adjunct for patients seeking minimal impact on gastrointestinal comfort. Alpha‑lipoic acid, although more costly, offers ancillary antioxidant benefits that may be advantageous for patients with diabetic neuropathy, a nuance that deserves further exploration. The tiered supplementation strategy proposed-starter, intermediate, power-provides a pragmatic roadmap, yet clinicians should individualize recommendations based on baseline glycemic control, comorbidities, and medication profiles. It is noteworthy that the article omits mention of potential contraindications for Karela in individuals on anticoagulant therapy, an oversight that could have clinical repercussions. Future research should prioritize large‑scale, double‑blind investigations that compare Karela directly against gold‑standard agents such as metformin, thereby clarifying its relative potency. Additionally, investigations into synergistic combinations, for example Karela with soluble fiber sources like glucomannan, may reveal additive effects on post‑prandial glucose excursions. In summary, the article delivers a balanced synthesis of current evidence while highlighting gaps that warrant rigorous scientific inquiry, and it equips readers with actionable insights for informed supplement selection.

Jocelyn Hansen

November 23, 2025 AT 08:22Great job laying out the pros and cons-it really helps to see the trade‑offs side by side! 😊 Remember, consistency is key, so whichever supplement you choose, pair it with a balanced diet and regular movement; your body will thank you. If you ever feel unsure, a quick chat with a healthcare professional can clear up any lingering doubts.

Joanne Myers

December 3, 2025 AT 19:33The table provides a succinct comparison of each agent’s active constituents and associated costs. Notably, berberine stands out for its extensive evidence base, while Karela offers a broader mechanistic profile albeit with less robust data.

rahul s

December 14, 2025 AT 06:45Listen up, folks! If you think a bitter‑melon splash can beat the mighty berberine, you’re dreaming in pink. Real science backs the alkaloid powerhouse, while Karela’s hype is just a marketing circus from a distant land. Choose the proven warrior, not the pretentious garnish.

Tommy Mains

December 24, 2025 AT 17:56For anyone starting out, I suggest mixing a small dose of cinnamon bark extract with chromium picolinate. This combo is cheap, easy on the stomach, and gives a gentle boost to insulin signaling. Track your fasting glucose weekly to see how you respond.

Alex Feseto

January 4, 2026 AT 05:07The exposition herein admirably collates extant literature; however, one must exercise discernment when extrapolating data derived from heterogeneous trial designs to a generalized cohort. A judicious appraisal of bioavailability and pharmacodynamics remains indispensable.

vedant menghare

January 14, 2026 AT 16:18Greetings, dear readers! Your curiosity about Karela’s place among natural glucose modulators is commendable, and the comparative insights provided are both enlightening and culturally resonant. May your health journey be guided by informed choices and a sprinkle of mindful optimism.

Kevin Cahuana

January 25, 2026 AT 03:29Keep tracking your numbers, and the data will speak for itself.

Danielle Ryan

February 4, 2026 AT 12:11Beware! The supplement industry is a labyrinth of hidden agendas!!! They push “miracle” extracts while cloaking potential interactions with prescription drugs-don’t be a pawn in their profit‑driven game!!!