When your heart skips, races, or feels like it’s fluttering in your chest, it’s not just discomfort-it’s a warning. Atrial fibrillation (AFib) is the most common heart rhythm disorder, affecting millions worldwide. Left untreated, it doesn’t just make you feel unwell-it quadruples your risk of stroke and increases your chance of dying by nearly double. The big question isn’t just whether to treat it, but how: should you focus on slowing the heart rate, or try to restore a normal rhythm? And what does that mean for your long-term risk of stroke?

What Is Atrial Fibrillation, Really?

Atrial fibrillation happens when the upper chambers of your heart (the atria) beat chaotically and out of sync with the lower chambers (ventricles). Instead of a steady, coordinated pulse, you get irregular, often rapid heartbeats. This messes up blood flow, causing clots to form-especially in the left atrial appendage. If a clot breaks loose, it can travel to your brain and cause a stroke.

AFib isn’t always obvious. Some people feel nothing. Others get dizzy, short of breath, exhausted, or have chest pain. The risk goes up with age, high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. But even younger, otherwise healthy people can develop it. And once you have it, the chance of stroke doesn’t disappear just because you feel fine.

Two Main Strategies: Rate Control vs. Rhythm Control

For decades, doctors had two clear paths:

- Rate control: Let the heart stay in AFib, but slow it down to a safe pace.

- Rhythm control: Try to restore and keep a normal heartbeat (sinus rhythm).

Back in the early 2000s, the AFFIRM trial changed everything. It showed that rate control worked just as well as rhythm control for survival. So, most patients were steered toward rate control-it was simpler, safer, and cheaper.

But things have changed. New drugs, better procedures, and newer trials have flipped the script.

Rate Control: Slowing Down, Not Fixing

Rate control doesn’t try to fix the rhythm. It just keeps your heart from racing too fast. The goal? Keep your resting heart rate under 110 beats per minute. Turns out, you don’t even need to get it below 80. The RACE II trial proved that lenient control (under 110 bpm) works just as well as strict control (under 80 bpm) for preventing hospitalizations, heart failure, and death.

Medications used:

- Beta-blockers (like metoprolol): First choice for most. They lower heart rate and reduce blood pressure.

- Calcium channel blockers (like diltiazem): Good for people who can’t take beta-blockers.

- Digoxin: Often used in older patients or those with heart failure, but less effective during exercise.

Amiodarone, once used for rhythm control, is also sometimes used in emergencies to quickly slow a fast AFib heartbeat-studies show it works faster and more reliably than digoxin in urgent situations.

Rate control is great for older adults, people with few symptoms, or those with other serious health problems. It’s easier to manage, has fewer side effects, and doesn’t require frequent monitoring. But here’s the catch: you still need blood thinners. Slowing your heart doesn’t stop clots from forming.

Rhythm Control: Trying to Get Back to Normal

Rhythm control aims to restore and maintain a normal heartbeat. This can be done with drugs or procedures.

Drug options:

- Flecainide and propafenone: Effective for paroxysmal AFib in people without heart disease.

- Dronedarone: Safer than older drugs like amiodarone, but not for people with severe heart failure.

- Amiodarone: Powerful but risky long-term-can damage lungs, thyroid, liver. Used when other drugs fail.

Procedures:

- Electrical cardioversion: A quick electric shock under sedation to reset the rhythm. Works well, but AFib often comes back.

- Catheter ablation: A thin tube is threaded into the heart to burn or freeze the spots causing the bad signals. Today, success rates are over 70% for paroxysmal AFib, with complication rates under 5%-down from 20% in the 2000s.

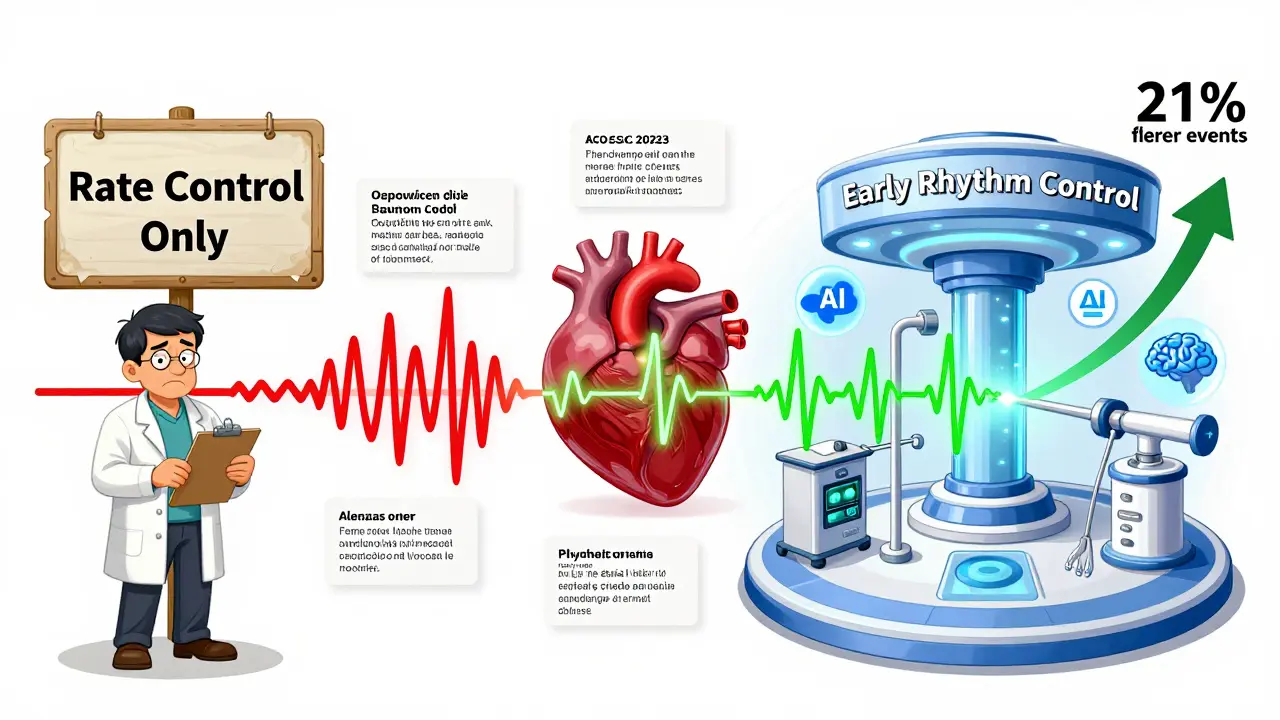

Why does this matter now? The EAST-AFNET 4 trial in 2020 changed the game. It followed nearly 2,800 patients diagnosed with AFib within the past year. Half got early rhythm control (drugs or ablation), half got usual care (rate control). After five years, the rhythm control group had 21% fewer heart-related deaths, strokes, heart failure hospitalizations, and heart attacks.

That’s not just a small win-it’s a major shift. For the first time, there’s solid proof that fixing the rhythm early can save lives.

Stroke Prevention: The One Thing You Can’t Skip

No matter which path you take-rate or rhythm control-you still need to prevent strokes. That means anticoagulants.

The CHA₂DS₂-VASc score is used to decide who needs blood thinners:

- 1 point each for: Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age 65-74, Diabetes, Vascular disease

- 2 points each for: Age 75+, Stroke or TIA

If your score is 2 or higher, you need a blood thinner-usually a DOAC (direct oral anticoagulant) like apixaban, rivaroxaban, or dabigatran. These are safer and easier than warfarin. They don’t need regular blood tests, and they work better at preventing strokes.

Here’s the scary part: In the AFFIRM trial, most strokes happened when patients stopped their blood thinners or their levels were too low. So even if you’re doing everything right-taking your meds, seeing your doctor-you can’t afford to skip anticoagulation.

Who Gets What? It’s Not One-Size-Fits-All

There’s no universal answer. Your age, symptoms, heart health, and lifestyle all matter.

Rate control is often the better first choice if:

- You’re over 75

- You have no symptoms or only mild ones

- You have other serious health issues (like kidney disease or lung disease)

- You’re not a good candidate for ablation

Rhythm control is now recommended earlier if:

- You’re under 65

- You have paroxysmal AFib (comes and goes)

- You’re still symptomatic despite rate control

- You have heart failure-even with preserved ejection fraction

- Your CHA₂DS₂-VASc score is 2 or higher

The 2023 European Society of Cardiology guidelines now say: “Early rhythm control should be offered to patients with AF regardless of symptom severity.” That’s huge. It means even if you feel fine, if you’re young and otherwise healthy, trying to fix the rhythm early might be the smarter long-term move.

The New Reality: Early Rhythm Control Is the Future

It’s no longer just about managing symptoms. It’s about preventing long-term damage. AFib doesn’t just cause clots-it can weaken your heart over time. The longer you stay in AFib, the harder it is to get back to normal. That’s why timing matters.

Studies now show that starting rhythm control within the first year of diagnosis leads to better outcomes. Ablation success rates are higher when done early. Antiarrhythmic drugs work better before the heart remodels. And the risk of complications from ablation has dropped dramatically.

Still, access isn’t equal. In rural areas or places with limited specialists, ablation might not be available. That’s why rate control remains a vital tool. But the trend is clear: rhythm control is moving from last resort to first option-for the right people.

What’s Next? The Future of AFib Treatment

Research is accelerating. The ASSERT II trial, due to finish in 2025, is looking at whether early ablation helps patients with AFib and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction-a group that’s been overlooked.

AI is also starting to help. Some hospitals now use machine learning to predict who’s most likely to benefit from ablation based on heart scans and genetic markers. Personalized treatment is coming.

And the market is responding. The global cardiac ablation market is expected to grow from $3.8 billion in 2022 to over $6 billion by 2028. More tools, better techniques, and wider access mean more people will have options.

For you, the takeaway is simple: Don’t assume one strategy is better for everyone. Talk to your doctor about your age, symptoms, risk of stroke, and long-term goals. If you’re under 75 and have AFib, ask: “Should I try rhythm control now?” The answer might just change your future.

Is rate control enough for atrial fibrillation?

Rate control is effective for many people, especially older adults or those with few symptoms. It reduces heart rate to a safe level and lowers the risk of heart failure. But it doesn’t stop clots from forming, so anticoagulation is still required. For younger, symptomatic patients or those with heart failure, early rhythm control may offer better long-term outcomes, including fewer hospitalizations and lower stroke risk.

Can rhythm control prevent stroke?

Rhythm control doesn’t directly prevent stroke-but it reduces the chance of long-term heart damage and heart failure, which lowers overall cardiovascular risk. The EAST-AFNET 4 trial showed that early rhythm control reduced stroke risk by 21% compared to rate control alone. However, anticoagulation is still needed regardless of the strategy chosen, because AFib can return even after rhythm is restored.

Which is safer: rate control or rhythm control?

Rate control is generally safer in the short term, with fewer side effects from medications and no procedural risks. Rhythm control, especially with ablation, carries small risks like bleeding or damage to heart tissue-but those risks have dropped to under 5% today. Antiarrhythmic drugs can cause serious side effects, but newer ones like dronedarone are much safer than older options like amiodarone. For healthy, younger patients, the long-term benefits of rhythm control often outweigh the risks.

Do I still need blood thinners if I have rhythm control?

Yes. Even if you’re in normal rhythm after ablation or cardioversion, you still need anticoagulation for at least 4 weeks-and often longer. AFib can recur silently, and clots can still form. Guidelines recommend continuing blood thinners based on your CHA₂DS₂-VASc score, not your current rhythm. Stopping anticoagulation too soon is one of the most common reasons for stroke in AFib patients.

When should I consider ablation for atrial fibrillation?

Ablation is now recommended earlier than before-especially if you’re under 75, have symptoms despite medication, or have heart failure. It’s most effective for paroxysmal AFib and when done within the first year of diagnosis. If you’re young, active, and want to avoid lifelong medication, ablation is a strong option. Talk to an electrophysiologist to see if you’re a candidate. Success rates are over 70% for early cases.

Branden Temew

December 31, 2025 AT 16:06So let me get this straight-we’re telling people with a heart that’s basically throwing a rave in their chest to just chill out and take a beta-blocker like it’s a yoga class? Meanwhile, the clot factory keeps running. I’m not saying we need to fix everything, but if we can stop the chaos before it turns into a cardiac civil war, why wait? Also, who decided 110 bpm was the new chill zone? My cat’s heart rate is lower than that when she’s napping on my keyboard.

Frank SSS

January 2, 2026 AT 05:22Honestly, I don’t care what the trials say. I had AFib for three years and just took my meds and didn’t think about it. Felt fine. Then one day I passed out in the grocery store. Turns out my INR was in the toilet. So yeah, rate control? Fine. But don’t forget the blood thinners. That’s the real silent killer here.

Brady K.

January 2, 2026 AT 09:28Rate control is the medical equivalent of putting duct tape on a leaking nuclear reactor and calling it a day. The EAST-AFNET 4 trial didn’t just ‘flip the script’-it set the whole damn theater on fire. We’re talking about preventing structural remodeling, reducing heart failure admissions, and cutting stroke risk by 21%. And yet, primary care docs are still treating AFib like it’s a seasonal allergy. If you’re under 75 and symptomatic, you’re not ‘managing’ AFib-you’re gambling with your longevity. Ablation isn’t a last resort anymore; it’s the upgrade you didn’t know you needed. Stop waiting for the ‘perfect time.’ Your heart isn’t waiting.

Marilyn Ferrera

January 2, 2026 AT 23:06Anticoagulation isn't optional. It's non-negotiable. Even if you're in sinus rhythm. Even if you feel fine. Even if your doctor says 'maybe.' CHA₂DS₂-VASc score ≥2? You're on a DOAC. Period.

Robb Rice

January 3, 2026 AT 05:21It's interesting how the guidelines have evolved. I used to think rate control was the gold standard, but now, after reading the latest ESC recommendations, I'm convinced that early rhythm control should be considered for nearly all patients under 75. I just wish more people had access to electrophysiologists. I think we need more education, not just for patients, but for family doctors too.

Harriet Hollingsworth

January 5, 2026 AT 02:14People are dying because they’re too lazy to take their blood thinners. You think your ‘natural remedies’ or ‘yoga breathing’ are gonna stop a clot? No. You’re just a walking stroke waiting to happen. If you have AFib and you’re not on a DOAC, you’re not being brave-you’re being stupid. And if your doctor isn’t pushing this, find a new one.

Lawver Stanton

January 6, 2026 AT 10:43Okay, so let me get this straight-there’s this whole thing where we used to just slow the heart down, and now we’re supposed to zap it back to normal with lasers and electricity? And we’re supposed to believe this is better? But then, why do I still need to take blood thinners forever? If the rhythm’s fixed, why am I still at risk? And why does it cost $30,000 to fix my heart when my car gets fixed for $2,000? Also, I’ve been on metoprolol for five years and I’m fine. Why does everyone suddenly think I need to get zapped? Is this just a big industry push? Are they selling ablation machines like iPhones now? Because if so… I’m not buying it. Not yet.

Sara Stinnett

January 8, 2026 AT 06:35Oh, so now rhythm control is ‘the future’? Funny how the same people who told us statins were the answer to everything are now selling us ablation like it’s the Holy Grail. Let’s not forget: amiodarone still wrecks your lungs, ablation still perforates hearts, and DOACs still cause internal bleeding. The truth? Medicine doesn’t fix biology-it just delays the inevitable. You think you’re ‘saving’ your heart by zapping it? You’re just buying more time before the next crisis. The real solution? Stop eating processed food. Stop sitting. Stop pretending your lifestyle doesn’t matter. But no-let’s keep selling procedures and pills. That’s where the money is.

linda permata sari

January 8, 2026 AT 14:37In my country, we don’t have ablation centers in every town. But we do have turmeric, garlic, and daily walking. My grandmother had AFib for 20 years-no meds, no shocks. She lived to 94. Maybe the real answer isn’t in the cath lab… maybe it’s in the kitchen, the garden, and the quiet morning breaths. We forget that sometimes, the body heals when we stop trying to force it.

Brandon Boyd

January 9, 2026 AT 18:14Look-I’m not a doctor, but I’ve been living with AFib for seven years. I did rate control first. Felt like a zombie on beta-blockers. Then I got ablated. It was scary. But now? I run marathons. I sleep through the night. I don’t think about my heart. And yes-I still take apixaban. But I’m alive, active, and not waiting for the next stroke. If you’re young, healthy, and tired of feeling like a broken machine… don’t wait. Talk to an electrophysiologist. It’s not magic. But it’s better than resignation.