Getting a generic drug approved isn’t just about matching the brand-name pill’s ingredients. It’s about proving your version behaves the same way in the body. That’s where bioequivalence (BE) studies come in. These clinical trials compare how fast and how much of a drug enters your bloodstream - measured by Cmax and AUC - between the test product and the reference product. But here’s the catch: if your study is underpowered, you might fail even if your drug works perfectly. And if you use too many people, you waste time, money, and expose more volunteers to unnecessary procedures. The difference between success and failure often comes down to one thing: getting the sample size right.

Why Sample Size Matters More Than You Think

Most people think a BE study is just a simple comparison. It’s not. It’s a statistical tightrope walk. You’re not trying to prove one drug is better. You’re trying to prove they’re the same - within a narrow range. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require the 90% confidence interval of the geometric mean ratio (test/reference) to fall entirely between 80% and 125%. If it doesn’t, the study fails - no matter how well the drug performs clinically.

That’s why power analysis isn’t optional. Power tells you the probability your study will correctly detect bioequivalence when it truly exists. A study with 80% power means there’s a 1 in 5 chance you’ll miss it. That’s too risky. Most regulators now expect 90% power, especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows. A 2021 FDA report found that 22% of rejected BE studies had inadequate power calculations. That’s not a small mistake. It’s a costly one. Repeat studies cost millions. Patients wait longer. Companies lose market access.

The Three Big Numbers That Decide Your Sample Size

There are three variables that control how many people you need in your BE study. Get these wrong, and your whole design collapses.

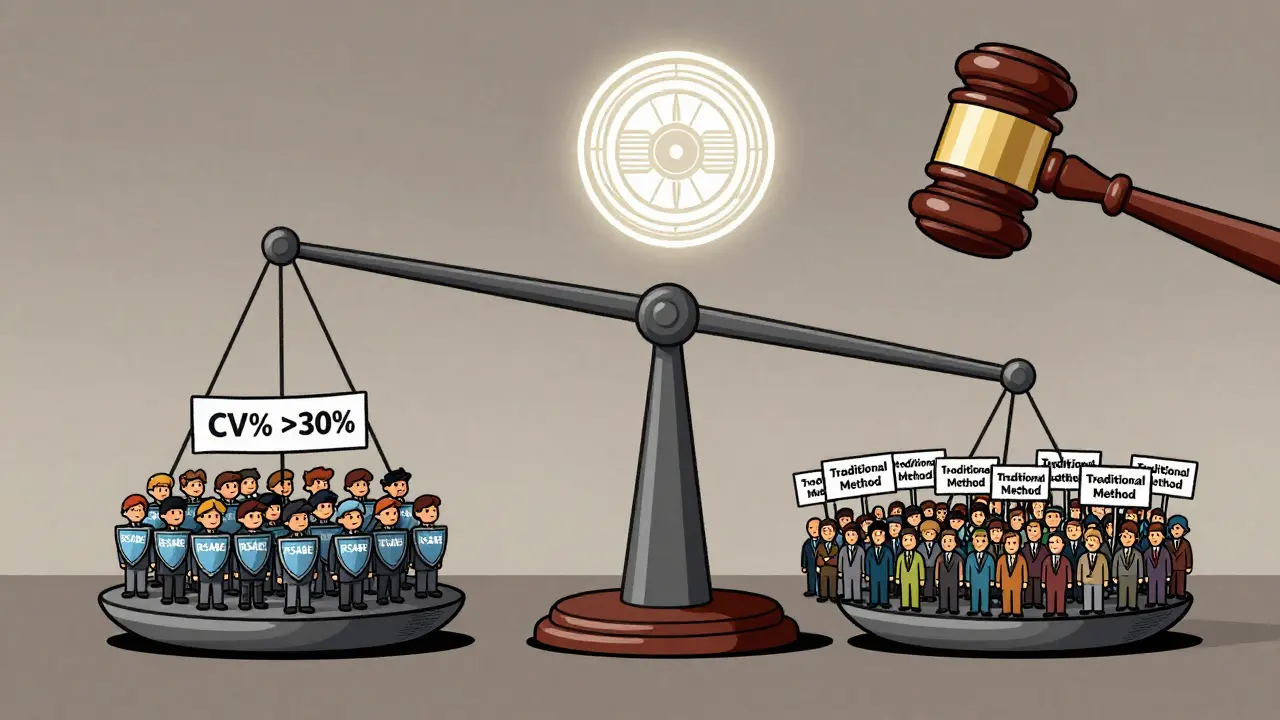

- Within-subject coefficient of variation (CV%): This measures how much a person’s own drug levels bounce around from dose to dose. For some drugs, like metoprolol, CV% might be 15%. For others, like warfarin or tacrolimus, it can be 40% or higher. The higher the CV%, the more people you need. A 20% CV might need 26 subjects. A 30% CV? That jumps to 52. And if you’re working with a highly variable drug over 30%, you might need to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which lets you widen the acceptance range based on variability - cutting your needed sample size in half.

- Expected geometric mean ratio (GMR): This is your best guess at how the test drug compares to the reference. Most generic manufacturers assume a 1.00 ratio - perfect match. But real-world data shows that’s rarely true. If your true GMR is 0.95 instead of 1.00, your required sample size can increase by 32%. Always use conservative estimates. Don’t rely on literature values. Pilot data is better. A 2019 study showed optimistic CV estimates caused 37% of BE study failures in oncology generics.

- Target power level: Is 80% enough? The EMA says yes. The FDA often wants 90%, especially for critical drugs. If you’re submitting globally, plan for 90%. It’s safer. And if you’re studying two endpoints - Cmax and AUC - you can’t just power for one. You need joint power. Only 45% of sponsors do this correctly. That means half of them are underestimating the real risk of failure.

How to Actually Calculate It - No PhD Required

You don’t need to memorize the formula, but you should understand what goes into it. The core calculation for a two-way crossover design looks like this:

N = 2 × (σ² × (Z₁₋α + Z₁₋β)²) / (ln(θ₁) - ln(GMR))²

Where:

- σ = within-subject standard deviation (derived from CV%)

- Z₁₋α and Z₁₋β = statistical constants for alpha (0.05) and power (0.80 or 0.90)

- θ₁ = lower equivalence limit (0.80)

- GMR = expected test/reference ratio

But you don’t have to do this by hand. Use tools built for this. ClinCalc’s BE Sample Size Calculator, PASS, nQuery, or FARTSSIE are all designed specifically for bioequivalence. They handle the log-normal distribution, crossover design, and regulatory margins automatically. Industry statisticians say 78% use these tools iteratively - tweaking the CV, GMR, and power to find the sweet spot between feasibility and compliance.

Here’s a real example: A generic version of a drug with a 25% CV, expected GMR of 0.98, and 90% power needs 42 subjects. But if you mistakenly use a 15% CV (from outdated literature), you’d calculate only 20 subjects. Your study fails. The FDA flags it. You’re back at square one.

What No One Tells You About Dropouts

People drop out. They get sick. They move. They change their mind. You can’t assume everyone will finish. If you calculate 40 subjects and 10% drop out, you’re down to 36 - which might be below the minimum needed to maintain power. Best practice? Add 10-15% extra. So if your calculation says 40, enroll 46. Document this decision. The FDA’s 2022 review template says incomplete dropout adjustments account for 18% of statistical deficiencies. That’s avoidable.

Don’t Ignore the Study Design

Most BE studies use a crossover design - each person gets both the test and reference drug, in random order. That’s powerful because it removes person-to-person variability. But it’s not foolproof. Sequence effects matter. If everyone gets the reference first, then the test, any carryover effect could bias results. That’s why washout periods are critical. And why you need to account for period effects in your analysis. The EMA rejected 29% of BE studies in 2022 for poor handling of sequence effects. This isn’t a minor detail. It’s a study killer.

Parallel designs - where one group gets the test and another gets the reference - are simpler but need way more people. You lose the within-subject control. So unless you’re studying a drug with a very long half-life, stick with crossover. Just make sure your design is documented, randomized, and blinded.

Regulatory Differences You Can’t Afford to Ignore

The FDA and EMA are similar, but not identical. The EMA allows a wider range (75-133%) for Cmax in certain cases, which can reduce sample size by 15-20%. The FDA doesn’t. If you’re targeting both markets, plan for the stricter standard. Also, the EMA accepts 80% power for most drugs. The FDA often expects 90% for narrow therapeutic index drugs like digoxin or levothyroxine. If you submit a study with 80% power to the FDA for one of these drugs, it will be rejected - no second chances.

And don’t assume global alignment. A 2023 study found that 40% of submissions that worked in Europe failed in the U.S. because of power or margin differences. Always check the latest guidance. The FDA’s 2023 draft on adaptive designs now allows sample size re-estimation mid-study - but only if you pre-specify the rules. This is advanced. Most companies aren’t ready. But if you are, it can save you from a failed trial.

Common Mistakes That Sink BE Studies

- Using literature CV% without validation: Literature values are often too low. The FDA found that 63% of submissions using literature CVs underestimated true variability by 5-8 percentage points.

- Assuming GMR = 1.00: That’s wishful thinking. Use real pilot data. Even a small shift from 1.00 to 0.95 changes everything.

- Powering only for AUC or Cmax: You need joint power. If AUC passes but Cmax fails, the study fails. Calculate for both.

- Not documenting your assumptions: The FDA wants to see your software, version, inputs, and why you chose them. If you can’t show your work, you’ll get a Complete Response Letter.

- Ignoring RSABE for highly variable drugs: If your CV is over 30%, don’t brute-force a huge study. Use RSABE. It’s approved. It’s efficient. And it’s designed for exactly this problem.

What’s Next? The Future of BE Power Analysis

Model-informed bioequivalence (MIBE) is coming. Instead of relying on traditional PK parameters, MIBE uses mathematical models to predict bioequivalence from sparse data. It could cut sample sizes by 30-50% for complex drugs like biologics or extended-release formulations. But as of 2023, only 5% of submissions use it. Regulatory uncertainty holds it back. But the FDA’s 2022 Strategic Plan for Regulatory Science is pushing for it. If you’re developing a new formulation, start learning about MIBE now.

For now, stick to the basics: use conservative estimates, power for both endpoints, account for dropouts, use validated tools, and document everything. The rules haven’t changed. The stakes have.

What’s the minimum sample size for a bioequivalence study?

For low-variability drugs (CV% under 10%) with a crossover design, 12-18 subjects may be sufficient. But for most drugs with CV% between 15-25%, you’ll need 24-36 subjects. Never go below 12 unless you have strong regulatory justification. Even then, regulators expect justification for small samples.

Can I use 80% power instead of 90%?

The EMA accepts 80% power for most drugs. The FDA usually expects 90%, especially for narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin, digoxin, or cyclosporine. If you’re submitting to both, plan for 90%. Using 80% for a U.S. submission increases your risk of rejection. It’s not a gamble worth taking.

How do I find the right CV% for my drug?

Don’t rely on published literature. Use pilot data from your own formulation. If you don’t have pilot data, use the highest CV% from similar drugs in the same class. The FDA found that literature CVs underestimate true variability by 5-8 percentage points in over 60% of cases. Better to overestimate than risk failure.

What’s RSABE and when should I use it?

RSABE stands for Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence. It’s a method that widens the 80-125% acceptance range based on how variable the reference drug is. Use it when the within-subject CV% is over 30%. It reduces the number of subjects needed from 100+ to 24-48. Both the FDA and EMA allow RSABE for highly variable drugs - but you must pre-specify the method in your protocol and justify it statistically.

Do I need to power for both Cmax and AUC?

Yes. You must calculate joint power - meaning the probability that both Cmax and AUC pass simultaneously. Most sponsors only power for the more variable parameter (often Cmax), which reduces the actual power of the study by 5-10%. If one endpoint fails, the entire study fails. Always calculate for both.

What software should I use for sample size calculation?

Use tools designed for BE studies: PASS, nQuery, FARTSSIE, or ClinCalc’s BE calculator. Avoid general power calculators. BE requires log-normal distributions, crossover designs, and regulatory-specific margins. These tools handle all that automatically. Document the software name and version in your protocol. The FDA requires it.

What happens if my BE study fails?

If your study fails due to inadequate power or sample size, you’ll get a Complete Response Letter from the regulator. You’ll need to redesign the study - with a larger sample, better assumptions, or a different method like RSABE. Repeat studies cost $1-3 million and delay market entry by 12-18 months. Prevention is cheaper than correction.

Final Checklist Before You Enroll Your First Subject

- Did I get CV% from pilot data, not literature?

- Did I use a conservative GMR (0.95-1.05), not 1.00?

- Did I power for 90% and both Cmax and AUC?

- Did I add 10-15% for dropouts?

- Did I use a BE-specific calculator and document the software?

- Did I justify my design choice (crossover vs. parallel)?

- Did I check if RSABE applies (CV% > 30%)?

- Did I document every assumption for the regulator?

If you answered yes to all of these, your study has a strong chance of passing. If not - go back and fix it. One mistake can cost you millions. Get it right the first time.

Janette Martens

December 30, 2025 AT 07:34Marie-Pierre Gonzalez

December 31, 2025 AT 17:57Louis Paré

January 1, 2026 AT 15:54Samantha Hobbs

January 2, 2026 AT 18:26sonam gupta

January 3, 2026 AT 23:24Julius Hader

January 5, 2026 AT 14:48Payton Daily

January 5, 2026 AT 17:43Kelsey Youmans

January 6, 2026 AT 07:59