When a pharmaceutical company changes even a small part of how it makes a drug-like swapping out a mixer, moving a step to a different room, or switching suppliers for an ingredient-it’s not just an internal operation. It’s a regulatory event. And if you get it wrong, you could face a warning letter, a product recall, or even a shutdown. The rules around manufacturing changes aren’t suggestions. They’re legally binding, and they vary by country. But the core idea is always the same: manufacturing changes must not compromise the safety, strength, quality, or purity of the medicine.

Why Do Manufacturing Changes Need Approval?

Think of a drug like a recipe. Even if you use the same ingredients, changing how you mix them, how long you heat them, or what container you use can alter the final product. In pharmaceuticals, that’s not just a minor tweak-it’s a potential risk to patients. A change in the drying temperature of a tablet might make it dissolve too slowly. A new supplier for an active ingredient could introduce impurities. A different sterilization method might kill off the bacteria, but leave behind toxins. Regulators like the FDA, EMA, and Health Canada don’t want companies guessing. They require proof that any change won’t hurt the patient. That’s why every change, no matter how small, has to be evaluated, documented, and reported. The goal isn’t to slow things down-it’s to prevent bad drugs from reaching shelves.How Are Manufacturing Changes Classified?

Most regulatory agencies use a tiered system. You don’t need to submit the same paperwork for every change. The level of review depends on risk. Here’s how it breaks down:- Major changes-These have a high chance of affecting the drug’s quality. Examples: switching the chemical synthesis route for the active ingredient, moving production to a new factory, or changing equipment that controls critical process parameters. These require prior approval. You can’t make the change until the regulator says yes.

- Moderate changes-These carry some risk but are less likely to cause harm. Examples: replacing a mixer with an identical model from the same manufacturer, updating software that controls a filling machine, or changing the packaging material if it doesn’t affect stability. These usually require notice before implementation-often 30 days in advance.

- Minor changes-These are low-risk and well-understood. Examples: reorganizing storage within the same facility, updating a non-critical label, or changing the supplier of a non-critical excipient with a proven track record. These don’t need advance notice. You just document them and report them once a year.

The U.S. FDA calls these categories: Prior Approval Supplement (PAS), Changes Being Effected in 30 Days (CBE-30), and Annual Report. The European Medicines Agency uses Type II (major), Type IB (moderate), and Type IA (minor). Health Canada uses Level I, II, and III. The names differ, but the logic is the same: higher risk = more oversight.

What Triggers a Major Change (PAS)?

You don’t get to decide if a change is major based on how easy it feels. You have to prove it. The FDA’s 2021 guidance for biologics gives clear examples. If you replace a lyophilizer (freeze-dryer) with a new one that has different pressure controls, that’s a PAS. Why? Because freeze-drying affects how the drug survives storage. Even if the new machine is “better,” if it changes a critical process parameter, you need approval first. Other major triggers:- Changing the synthesis method for an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)

- Adding a new manufacturing site for a critical step

- Switching from batch to continuous manufacturing

- Modifying the final sterilization process

In 2023, the FDA issued four warning letters specifically for companies that treated major equipment changes as minor. One company replaced a lyophilizer without a PAS. The product was already distributed. The FDA shut down the batch. The company lost months and millions.

What Counts as a Moderate Change (CBE-30)?

This is where most companies get tripped up. It’s not about the size of the change-it’s about the impact. Replacing a tablet press with an identical model from the same manufacturer? That’s usually CBE-30. But if the new press has a different compression force control system, and that affects tablet hardness (a critical quality attribute), it becomes a PAS. The FDA says “equivalent” means:- Same principle of operation

- Same critical dimensions

- Same material of construction

If any of those change, you’re likely in PAS territory. A senior regulatory affairs specialist at a mid-sized generic company told me they spent 37 hours debating whether a new tablet press counted as equivalent. Why? Because the API had inconsistent particle size. Even a small change in compression could alter dissolution rates. That’s why you need data-not gut feeling.

Documentation Is Non-Negotiable

You can’t just say, “We changed it.” You have to prove it was safe. For any moderate or major change, you need:- Facility diagrams showing where the change occurred

- Process validation reports comparing old and new methods

- Comparative data from at least three consecutive batches made after the change

- Stability data showing the drug still meets shelf-life specs

- A risk assessment using tools like FMEA (Failure Modes and Effects Analysis)

One company in 2022 skipped the stability testing for a minor change to their packaging. Six months later, customers reported the tablets were crumbling. The batch was recalled. The FDA cited them for failing to perform adequate comparability studies.

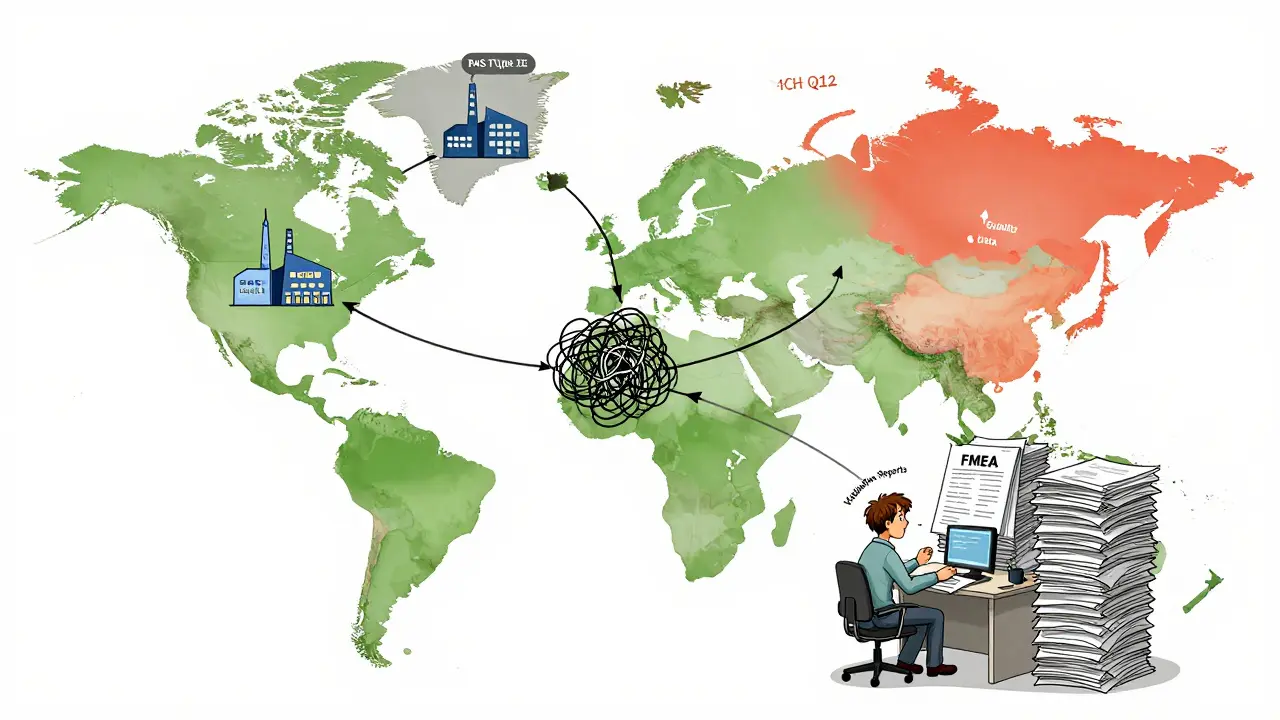

How Do Global Rules Compare?

The U.S., Europe, and Canada all have similar systems-but the timing and flexibility differ.| Change Type | U.S. FDA | European EMA | Health Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Prior Approval Supplement (PAS) | Type II (Full review before implementation) | Level I (Prior approval required) |

| Moderate | CBE-30 (Notify 30 days before) | Type IB (Approval before implementation, no fixed timeline) | Level II (Notify and wait) |

| Minor | Annual Report | Type IA (Notify within 12 months) | Level III (Annual notification) |

Europe allows some minor changes (Type IA) to be implemented before notification. The U.S. doesn’t. That’s a big difference. Companies operating globally have to run two systems. One for the U.S., one for Europe. It’s messy. That’s why the ICH Q12 guideline, adopted in 2020, was created-to harmonize these rules. Progress is slow, but it’s happening.

What Happens If You Get It Wrong?

In 2022, 22% of all FDA warning letters were about manufacturing changes. Of those, 37% were due to misclassifying equipment changes. One company changed the solvent used in a cleaning process for a vial filler. They called it a minor change. The FDA said it altered the risk of residue contamination. The company got a warning letter. Their product was recalled. Their stock dropped 15%. The FDA doesn’t just penalize. They also give second chances-if you act fast. If you realize you misclassified a change, you can submit a supplemental application immediately. But you have to stop distribution. You can’t sell the product while you fix the paperwork.

Who’s Responsible?

This isn’t just the job of the regulatory affairs team. It’s a team sport. You need:- Quality Assurance-To flag any change and ensure documentation

- Manufacturing-To know exactly what was changed and why

- Validation-To prove the change didn’t break anything

- Regulatory Affairs-To file the right paperwork

- Supply Chain-To track new suppliers or materials

According to a 2021 PDA study, a moderate change takes about 120 hours of team effort. That’s three full weeks of work for one person. For small companies, that’s a huge burden. Many don’t have the staff. That’s why compliance rates are only 63% among mid-sized firms, compared to 98% at big pharma.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance pushes for more use of quality risk management (ICH Q9). That means using data-not just rules-to decide how to classify changes. If you’ve got 10 years of stable production data on a piece of equipment, you might not need a full PAS for a minor upgrade. Also, continuous manufacturing is growing. In these systems, every machine is connected. Change one part, and it affects the whole line. That’s why the FDA says most continuous manufacturing changes now require PAS. It’s not just the equipment-it’s the system. By 2025, 40% of new change submissions are expected to include real-time quality monitoring data. That’s data from sensors during production showing the product stayed within specs. It’s proof, not paperwork.What Should You Do?

If you’re in pharma manufacturing, here’s what to do:- Don’t make any change without a risk assessment.

- Use FMEA or another formal method to score the impact on critical quality attributes.

- Check the latest FDA, EMA, or Health Canada guidance before classifying.

- When in doubt, ask the regulator. The FDA encourages early consultation.

- Document everything-even the changes you think are too small to matter.

- Train your team. Regulatory affairs specialists need 18 months of focused training to get this right.

Manufacturing changes aren’t about slowing down innovation. They’re about protecting people. The rules are strict because the stakes are high. Get it right, and you keep your product on the market. Get it wrong, and you risk lives-and your company’s future.

What happens if I make a manufacturing change without notifying the regulator?

You could face a warning letter, product recall, or even a halt to production. The FDA and other regulators monitor distribution records and can trace unapproved changes back to specific batches. If they find you made a major change without prior approval, they can order you to stop shipping the product immediately. In 2023, four companies received warning letters for exactly this.

Can I change equipment without a new approval if it’s the same model?

Only if it’s truly equivalent: same principle of operation, same critical dimensions, and same material of construction. Even then, you usually need to file a CBE-30 (in the U.S.) or notify the regulator before implementation. You must also validate that the new equipment produces the same quality product. Just swapping a machine with the same model number isn’t enough-validation data is required.

How long does it take to get approval for a major manufacturing change?

For a Prior Approval Supplement (PAS) in the U.S., the FDA has 180 days to review. But if they ask for more data, the clock resets. In practice, many take 6-12 months. In Europe, Type II changes can take 60-120 days. The timeline depends on how complete your submission is. Companies that do early consultations and provide full comparability data often get faster reviews.

Do small companies have to follow the same rules as big ones?

Yes. Regulatory requirements apply to everyone, regardless of size. But small companies often struggle because they lack dedicated regulatory teams. The FDA has programs to help, like the Small Business Assistance Program and pre-submission meetings. Still, 63% of small and mid-sized firms fail inspections due to change control issues, compared to 2% of large companies.

What’s the most common mistake companies make with manufacturing changes?

Assuming a change is minor because it’s small. Replacing a pump, moving a lab, or changing a label might seem insignificant-but if it affects a critical quality attribute like purity, dissolution, or sterility, it’s not minor. The biggest violations come from underestimating risk. Always use a formal risk assessment. Don’t rely on gut feeling.

Olukayode Oguntulu

January 2, 2026 AT 21:10Look, I get it-pharma’s got rules tighter than a Nigerian diplomat’s handshake. But let’s be real: if you’re swapping a mixer and the API doesn’t turn into a toxic sludge, why the hell do we need a 120-hour audit? This isn’t rocket science, it’s chemistry with a paperwork fetish. We’re drowning in compliance theater while real innovation dies in the queue.

ICH Q12? Cute. Until regulators stop treating every change like it’s a bio-terror plot, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic of bureaucracy.

Also, ‘minor change’ is a euphemism for ‘we didn’t want to call HR.’

Dusty Weeks

January 3, 2026 AT 05:07bro i just changed the label on my vitamin bottle and now i’m scared i’m gonna get a warning letter 😭😭😭

also why does every pharma doc sound like they’re reading a subpoena? i just wanna know if my pills are gonna kill me or not

Sally Denham-Vaughan

January 4, 2026 AT 10:02As someone who’s worked in a small lab where we didn’t have a dedicated regulatory person, I feel this so hard. We once replaced a stirrer and spent three weeks debating if it was ‘equivalent’-turns out the old one had a tiny scratch that made it ‘non-equivalent’ lol.

Here’s the thing: most of these rules exist because someone’s kid got sick from a bad batch. So yeah, it’s annoying. But it’s also sacred. We owe it to patients to get it right-even if it means 18 months of paperwork.

Big pharma has teams for this. Small shops? We’re all just winging it with Excel sheets and hope.

Also, if you’re a small company: use the FDA’s pre-submission program. It’s free. And they actually answer. I promise.

Bill Medley

January 5, 2026 AT 02:25Regulatory compliance is not optional. It is the ethical baseline of pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Every change, regardless of perceived scale, carries potential risk to human health.

Documentation is not bureaucracy-it is accountability.

Failure to comply is not negligence-it is endangerment.

There is no ‘too small’ when the patient is watching.

Richard Thomas

January 6, 2026 AT 21:35There’s a quiet tragedy here, buried under all the jargon and compliance checklists. We’ve turned medicine into a legal contract between corporations and regulators-and in the process, we’ve forgotten that the patient isn’t a variable in a validation report. They’re a person. They’re someone’s mother, their son, their neighbor who just wants to sleep without pain.

When we obsess over whether a new mixer is ‘equivalent’ to the old one, we’re not just measuring torque or material density-we’re measuring our humanity. Did we ask if the change made the drug gentler? Did we consider the elderly patient who struggles to swallow a harder tablet? Did we think about the single mother who can’t afford a recall-induced price hike?

The system isn’t broken because it’s too strict. It’s broken because we’ve stopped asking the human questions. We optimize for audit readiness, not healing.

Maybe if we trained regulatory staff in bedside manner instead of GMP forms, we’d get better outcomes.

I don’t know the answer. But I know we’re missing the point.

Ann Romine

January 8, 2026 AT 04:47Interesting how the EU lets you implement Type IA changes before notifying. That’s… bold. In the U.S., if you so much as change the font on a label, you’re supposed to file something. But in Europe, you can swap out a whole supplier for a non-critical excipient and just send an email later? That’s either brilliant risk-based thinking or a regulatory loophole waiting to explode.

Do you think this flexibility leads to more innovation-or more mistakes? I wonder if the EU’s system is just better at trusting industry, or if they just have more inspectors.

Also, I’m curious: has anyone studied whether countries with looser pre-notification rules have higher recall rates? It’d be a fascinating paper.

Todd Nickel

January 8, 2026 AT 16:29Let’s talk about the elephant in the room nobody wants to name: the real cost of change control isn’t the paperwork-it’s the talent drain. Every time a scientist or engineer has to spend three weeks filling out a comparability protocol instead of designing a new formulation, we lose innovation momentum.

And it’s not just the time-it’s the psychological toll. People start seeing every tweak as a potential career-ending misstep. They stop experimenting. They stop improving. They stop caring because the system punishes curiosity.

I’ve seen brilliant process engineers quit pharma because they couldn’t stand the fear. They went to biotech startups where the motto is ‘move fast and fix later.’ And honestly? Sometimes that’s the only way to break through.

The FDA’s draft guidance on risk-based change classification is a step in the right direction. But it’s still just guidance. Until it’s codified, and until companies are rewarded for transparency-not punished for honesty-we’re just dancing around the real problem.

Maybe the real ‘major change’ we need is to stop treating people like compliance robots and start treating them like problem-solvers.

Austin Mac-Anabraba

January 9, 2026 AT 04:08Let me be blunt: 90% of these ‘minor changes’ are just lazy companies trying to avoid real validation. You think replacing a pump is ‘minor’? Tell that to the patient whose drug dissolved at 30% instead of 85% because the new pump had 0.2% more vibration. You don’t get to decide what’s minor. The data does.

And if you’re a small company saying ‘we can’t afford the team’-then don’t make changes. Don’t pretend you’re a pharma company. You’re not. You’re a hobbyist with a laminated GMP poster.

Regulators aren’t the enemy. The people who think compliance is a ‘burden’ are. Stop whining. Do the work. Or get out.