Malignant Hyperthermia Drug Safety Checker

Check if Anesthesia Drugs Trigger Malignant Hyperthermia

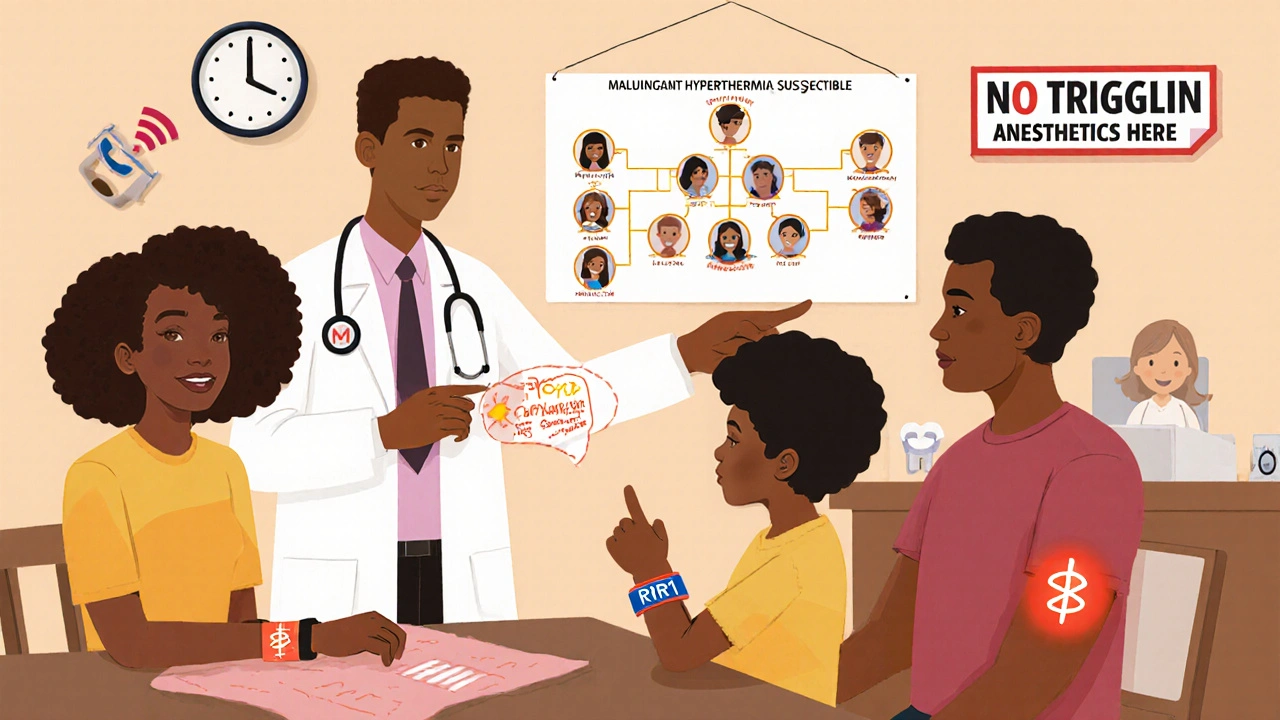

Malignant hyperthermia is a life-threatening reaction to certain anesthetic drugs. Check if your procedure uses triggering agents or safe alternatives.

Important Information

Malignant hyperthermia is a rare genetic reaction to certain anesthetic drugs. It can be fatal if not treated immediately with dantrolene.

If you have a family history of anesthesia complications or suspect MH risk, always inform your anesthesiologist before any procedure.

Imagine going in for a routine surgery-maybe a tonsillectomy or wisdom tooth removal-and waking up in a medical emergency you never saw coming. Your heart is racing, your body is overheating, your muscles are locked tight, and your blood is turning acidic. This isn’t a nightmare. It’s malignant hyperthermia, a rare but deadly reaction to common anesthesia drugs. And it can happen to anyone-even if they’ve had anesthesia before with no issues.

What Exactly Is Malignant Hyperthermia?

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a genetic condition that turns normal anesthesia into a medical crisis. It doesn’t cause problems on its own. But when someone with the right genetic mutation gets exposed to certain anesthetic gases or muscle relaxants, their muscles go haywire. Calcium floods out of storage in muscle cells, causing uncontrolled contractions. This isn’t just cramping-it’s a full-body metabolic explosion. The result? Body temperature can spike from normal to over 109°F (43°C) in minutes. Oxygen use skyrockets. Carbon dioxide builds up. Potassium leaks into the blood. Muscles break down, releasing toxins that can shut down kidneys. Without quick action, it’s often fatal. This isn’t theoretical. In the 1960s, four young Australians died during surgery under identical conditions. That’s when Dr. Denborough first linked these deaths to anesthesia. Since then, we’ve learned MH affects about 1 in every 5,000 to 100,000 procedures. But in kids having tonsillectomies, the risk jumps to 1 in 3,000. And here’s the scary part: nearly 3 out of 10 cases happen in people with no family history of MH. You can be perfectly healthy, have zero symptoms, and still carry the gene.Which Anesthesia Drugs Trigger MH?

Not all anesthesia causes this. Only specific drugs are triggers. The biggest culprits are:- Volatile anesthetic gases-sevoflurane, desflurane, isoflurane (all end in “-flurane”)

- Succinylcholine-a fast-acting muscle relaxant often used to help intubate patients

How Do You Know It’s Happening?

MH doesn’t announce itself with a warning sign. It creeps up fast. The earliest clue? A sudden, unexplained rise in heart rate-often over 120 beats per minute. Then comes a spike in carbon dioxide (ETCO2) levels, even if the patient is breathing fine. That’s because muscles are burning oxygen and producing CO2 like a furnace. Next, you might notice muscle rigidity, especially in the jaw. That’s called masseter spasm. It’s a red flag anesthesiologists watch for during induction. If a patient’s jaw locks up after succinylcholine, it’s a strong hint MH is starting. Within minutes, body temperature begins to climb. Blood tests show acidosis, high potassium, and skyrocketing creatine kinase (CK)-often over 10,000 U/L (normal is under 200). Urine turns dark brown or red from muscle breakdown products. This is when organ failure becomes a real risk. Symptoms usually show up within an hour of exposure. But in rare cases, they can appear hours later-even up to 24 hours after surgery. That’s why monitoring doesn’t stop just because the procedure is over.

The Only Treatment: Dantrolene

There’s only one drug that stops MH in its tracks: dantrolene. It works by blocking calcium release in muscle cells. No dantrolene? No survival. The standard dose is 2.5 mg per kilogram of body weight, given intravenously. If symptoms don’t improve within 5-10 minutes, you give another dose. Most patients need 5-10 mg/kg total. In severe cases, doctors may give up to 10 mg/kg-sometimes even more. But here’s the catch: dantrolene isn’t easy to use. The old version, Dantrium®, takes 22 minutes to mix. That’s too long when every second counts. The newer version, Ryanodex®, comes as a powder that dissolves in under a minute. It’s now the gold standard. Each vial costs about $4,000. A full emergency cart needs 36 vials-that’s $144,000 just for the drug. Hospitals are required to keep this stock ready. The FDA mandated it in 2021. But compliance varies. Urban hospitals with big budgets often have carts ready in under 30 seconds. Rural clinics? Some still don’t have enough on hand. In 2022, over 20% of rural hospitals reported running out of dantrolene.What Else Do You Do When MH Strikes?

Dantrolene is critical-but it’s not the whole plan. You need a full emergency protocol:- Stop all triggering anesthetics immediately. Switch to 100% oxygen.

- Hyperventilate the patient at 10 liters per minute to flush out CO2.

- Start cooling-ice packs on neck, armpits, groin. Cold IV fluids. Sometimes even extracorporeal cooling.

- Treat complications: Sodium bicarbonate for acidosis, insulin and glucose for high potassium, mannitol and furosemide to protect kidneys.

- Transfer to ICU-MH doesn’t just vanish. Patients need 24-48 hours of monitoring for rebound hypermetabolism.

How Do You Know If You’re at Risk?

Genetic testing for RYR1 and CACNA1S mutations is available. It costs between $1,200 and $2,500. Sensitivity is about 95% for known mutations-but not all mutations are identified yet. So a negative test doesn’t guarantee safety. The gold standard for diagnosis is the caffeine-halothane contracture test (CHCT), done on a muscle biopsy. But it’s invasive, expensive, and only available at a few specialized centers. Most people never get tested unless they’ve had a previous MH episode or a close relative has. That’s why the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends asking every patient about family history of anesthesia complications. If someone says, “My uncle died during surgery,” or “My brother had a bad reaction,” that’s a red flag. But here’s the problem: 68% of MH survivors had never heard of the condition before their own crisis. They didn’t know to ask. Their doctors didn’t know to dig deeper.

What Happens After You Survive?

Surviving MH doesn’t mean you’re out of the woods. You’re now at risk for future episodes. You must:- Get a medical alert bracelet that says “Malignant Hyperthermia Susceptible”

- Carry a wallet card with your diagnosis and emergency contact info

- Inform every doctor, dentist, or surgeon before any procedure

- Avoid all triggering agents forever

What’s New in MH Management?

The field is changing fast. In 2024, the FDA approved an intranasal form of dantrolene for use before hospital arrival-think paramedics giving it in ambulances. That could cut response time dramatically. Anesthesia machines now come with smart alerts. Epic Systems’ 2024 update automatically flags MH when three signs appear together: rising CO2, fast heart rate, and high temperature. It’s like a built-in alarm system. Researchers are testing new drugs like S107 that stabilize the ryanodine receptor. And long-term, CRISPR gene editing might one day fix the RYR1 mutation itself. Phase I trials are expected by 2027. But for now, the most powerful tool is awareness. The Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States (MHAUS) runs a 24/7 hotline (1-800-644-9737). Anesthesiologists call it when they’re unsure. It’s saved countless lives.What You Can Do

If you’re scheduled for surgery:- Ask your anesthesiologist: “Do you have dantrolene on hand?”

- Ask: “Have you ever treated a case of MH?”

- Share your family history-even if it seems unrelated

- Request non-triggering anesthesia if you’re at risk

- Get tested. Even if you’re not sure.

- Register with the North American MH Registry.

- Make sure your primary care doctor knows.

Can you develop malignant hyperthermia later in life if you’ve had anesthesia before without issues?

Yes. Malignant hyperthermia is genetic, so you’re born with the risk. But it only triggers when you’re exposed to certain anesthetics. Many people have multiple surgeries with no problems because they never received triggering drugs. Once you’re exposed and react, you’re diagnosed. But if you’ve never had a trigger, you might never know you’re at risk-until it’s too late.

Is malignant hyperthermia the same as a bad reaction to anesthesia?

No. Most “bad reactions” are allergic responses-rashes, low blood pressure, breathing trouble. MH is completely different. It’s a metabolic storm inside your muscles caused by a genetic flaw. It doesn’t involve the immune system. It’s not an allergy. It’s a runaway chemical reaction that can kill in minutes.

Does having a family member with MH mean I have it too?

Not necessarily. MH follows an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning if one parent has the gene, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it. But not everyone with the gene reacts. Some people carry the mutation and never have a reaction, even with triggering drugs. That’s why testing and family history matter-but they’re not foolproof.

Can dental procedures trigger malignant hyperthermia?

Yes. Any procedure using general anesthesia with sevoflurane, desflurane, isoflurane, or succinylcholine can trigger MH-even a simple tooth extraction. Many dental surgeries use these drugs. If you’re at risk, ask your dentist for alternatives like nitrous oxide and local anesthesia. Always disclose your MH history.

Is dantrolene safe for everyone?

Dantrolene is safe when used correctly in an MH emergency. But it can cause liver damage if given repeatedly or in high doses over days. That’s why it’s only used when MH is strongly suspected. It’s not a drug you take casually. In a crisis, the risk of not using it is far greater than the risk of using it.

What happens if a hospital doesn’t have dantrolene?

Without dantrolene, survival chances drop sharply. In the past, patients died because hospitals didn’t stock it. Today, U.S. regulations require all facilities performing general anesthesia to have an MH emergency kit. But compliance isn’t universal. Rural and small clinics sometimes lack the budget or awareness. That’s why calling the MHAUS hotline (1-800-644-9737) during a suspected case is critical-they can guide you to nearby hospitals with stock.

Tiffany Fox

November 27, 2025 AT 21:23Just had my kid’s tonsillectomy last month. They used propofol instead of the scary gases-asked point blank if they had dantrolene. Staff looked at me like I was crazy but had it ready. Good call.

Rohini Paul

November 29, 2025 AT 00:00I’m from India and we rarely see this discussed here. Our anesthesiologists just use ketamine + local for kids. No idea if they even know what MH is. Scary how unaware some places are.

Natalie Sofer

November 29, 2025 AT 16:22My uncle died during a wisdom tooth removal in the 90s. They said it was "heart failure" but now I think it was MH. No one ever connected the dots. I wish I’d known sooner. I got tested last year-positive for RYR1. Now I carry my card everywhere. Don’t let ignorance kill you.

Courtney Mintenko

November 30, 2025 AT 20:55So we’re just supposed to trust hospitals with 144k worth of drug sitting in a fridge like some kind of medical holy grail? Capitalism turns life saving meds into luxury items. Also why is dantrolene so expensive? Because someone decided it should be

Khamaile Shakeer

December 1, 2025 AT 15:33Okay but… what if you’re just allergic to dantrolene?? 😅 Like… what’s Plan B?? 😵💫 Also I had a tonsillectomy in 2018 and they used sevoflurane. I’m still here. So… maybe it’s not that bad?? 🤷♂️

Suryakant Godale

December 2, 2025 AT 20:21It is imperative to underscore that the genetic predisposition to malignant hyperthermia remains underdiagnosed in populations with limited access to specialized diagnostic facilities. The caffeine-halothane contracture test, though invasive, remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis. It is therefore essential that healthcare systems prioritize equitable access to such testing.

John Kang

December 4, 2025 AT 07:46My sister’s a nurse in a rural ER. She told me their hospital didn’t have dantrolene until last year. They got a grant. You’d be shocked how many places still don’t. If you’re getting surgery, ask. Don’t be shy. It’s your life.

Simran Mishra

December 5, 2025 AT 20:52I used to work in a surgical unit and once we had a case-man was 28, healthy, never had issues before. They gave him succinylcholine for intubation and his jaw locked like a vice. We didn’t have dantrolene on hand because the cart was in storage for "maintenance." We had to call three hospitals before one sent it by ambulance. He survived but spent six weeks in ICU. His wife cried in the hallway for hours. I still think about it. I don’t sleep well sometimes. We’re so unprepared. So many people don’t know. And it’s not just about the drug-it’s about the culture of ignoring rare things until they kill someone.

ka modesto

December 7, 2025 AT 02:10Big shoutout to MHAUS! I called them last year after my genetic test came back positive. They sent me a free medical bracelet and a whole packet of info for my dentist. They even called my surgeon’s office for me. Real heroes.

Holly Lowe

December 7, 2025 AT 10:52Imagine your body turning into a nuclear furnace during a tooth extraction. That’s not horror fiction-that’s Tuesday for some folks. And the fact that we’ve got a miracle drug that costs more than a used car but still isn’t guaranteed to be there? That’s not medicine. That’s a glitch in the system.

Cindy Burgess

December 8, 2025 AT 15:04While the article presents a comprehensive overview of malignant hyperthermia, it is noteworthy that the regulatory mandates concerning dantrolene stockpiling, although commendable, are not uniformly enforced across all jurisdictions. Furthermore, the absence of standardized preoperative screening protocols for genetic susceptibility remains a critical gap in preventive care.

Orion Rentals

December 8, 2025 AT 21:46Thank you for the detailed and scientifically accurate overview. I would like to add that the 2024 intranasal dantrolene formulation represents a significant advancement in pre-hospital emergency response. In rural settings, where transport times to tertiary care centers exceed 45 minutes, this innovation may significantly improve survival outcomes. I encourage all emergency medical services to adopt this protocol immediately.